Hail Caesar: Creative Commons and the Small Press

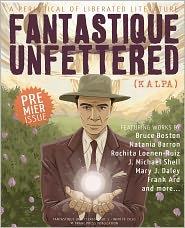

This is a guest post by Brandon H. Bell, editor of Fantastique Unfettered, which he publishes under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike license. In this post he explains why. We’re running it not because we agree with everything in it, but because we agree so strongly with his main points: that releasing works under freedom-friendly terms is compatible with profitability and helps deserving works avoid obscurity. It’s great to see a small press fully embrace this. The rest is by Brandon H. Bell…

Hail Caesar: Creative Commons and the Small Press

“It is not these well-fed long-haired men that I fear, but the pale and the hungry-looking.”

–Julius Caesar

- Write story

- Get said story published

- Profit! Karma!

I believe short fiction is important. The small press magazine I edit (Fantastique Unfettered, aka FU) uses a Creative Commons license, CC-BY-SA, for reasons related to this view, and in service to the dual end-goals of money and karma on behalf of the writers we publish.

Our alignment

This article will appear in the second issue of FU, but I hope it’s not where you originally read it. You see, it carries the same CC-BY-SA license. A Creative Commons, Attribution, ShareAlike license, meaning that others can do pretty much anything they want with the article, but they must give attribution and release under the same. Each instance of a presentation, adaptation, or derivative of the article is, essentially, a finger pointed back at FU. Um, not that finger.

The old world-think of walled gardens and content farms suggests the only way forward is copyright extensions, possibly to perpetuity. Our old-thinkers recognize the current audience is merely the first audience. It’s a numbers game, and while individual creators will not make much to crow over statistically, the bulk IP of the mass of creators certainly will. These Caesars would own human culture, every song a commercial jingle, every myth protected by a (TM).

I’m not an ideologue; I’ve stated in blog posts that I don’t know how well CC-BY-SA scales, and for the Stephen Kings of the world, traditional copyright may be the only reasonable default for their work. Creative Commons is a tool, in a toolbox that includes traditional copyright, and I have no prohibition against the latter (though even if I reach “rockstar” level, I would ensure my work returns to the culture at some point).

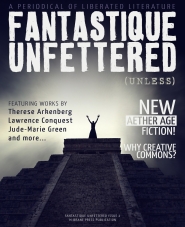

With Aether Age (our first CC-BY-SA project, a shared world of space-faring Greeks and social revolutions in Egypt) we’ve made the work immediately available to the culture. The same is true of FU. The same will be true of my novella, Elegant Threat, to be released in the M-Brane Double #1 later this year. The New People by Alex Jeffers, the other half of the Double, will carry a traditional copyright. My first novel may carry a traditional copyright, depending on the publisher.

Writers deserve to be paid for their work, and we hope that you, dear reader, will take an active interest in supporting short fiction. If not FU, then some other venue. As a writer, I hope to someday make loads of cash at my craft and to have people bemoan my place on the NYT list. That hack, they’ll complain as I laugh my way to the bank. (Yeah, it’s a writer thing.) So, a final reminder that our use of Creative Commons licensing is not purely ideological or a revolt against traditional publishing.

Writers deserve to be paid for their work, and we hope that you, dear reader, will take an active interest in supporting short fiction. If not FU, then some other venue. As a writer, I hope to someday make loads of cash at my craft and to have people bemoan my place on the NYT list. That hack, they’ll complain as I laugh my way to the bank. (Yeah, it’s a writer thing.) So, a final reminder that our use of Creative Commons licensing is not purely ideological or a revolt against traditional publishing.

Creative Commons licensing does not rob writers of ownership of their work, the ability to publish it in anthologies, collections, or even to waive the license to accommodate incoming requests to publish/adapt under other terms.

The license is a tool to reach readers, and to proclaim cultural relevance to the future. Maybe our work, and work like it, becomes an island of open/libre culture in a future of copyrighted IP masquerading as culture. We intend to run FU much like a nonprofit (though it isn’t a nonprofit), to not profit off the periodical ourselves, but to use any incoming funds to make FU self-sustaining, then better pay our contributors.

CC-BY-SA is a tool for proactively freeing art to the culture, and will be right for some projects, and wrong for others. It is a tool for generating karma and reaching more readers. The other CC licenses and traditional copyright are also valid tools.

While the small press is a valuable part of the greater cultural ecosystem, big publishers (and big writers) are our heroes. Copyright is, ultimately, agnostic, insofar as it allows creators and their families to benefit from their work. The same is true of Creative Commons, and use of CC licenses does not preclude profitability.

It would be easy to stop there, with that pithy statement ignoring the real challenge we face in obscurity. The small press is a playground for the new, the odd, the possibly non-commercial (or not commercial right now), the niche. The small press bears the responsibility to pursue the mandates of a given niche while striving for a quality of content, presentation, and a dedication to the idea that if anyone should be hungry and unsatisfied with imitation and shallowness, the merely commercially viable, it is us.

To close on a theme, perhaps our Caesar is that societal voice addressed to those who would participate in the culture, that suggests: you are a consumer, only.

We have come not to praise Caesar, but to bury him.

Please steal this article and post anywhere you like, just provide attribution and keep it under the same license. Encourage others to do the same. [2]

Footnotes

[1] See the Tim O’Reilly article here http://openp2p.com/lpt/a/3015

[2] CC-BY-SA for the license, and for attribution: Brandon H. Bell, editor, Fantastique Unfettered, http://www.fantastique-unfettered.com/.

Contact Brandon at editors {_AT_} fantastique-unfettered.com and check out “our first CC-BY-SA project, The Aether Age: Helios, edited by Christopher Fletcher and myself and published by Hadley-Rille Books.”

Dear Authors,

Dear Authors,

The result: thousands of remixes and millions of downloads. Relinquishing tight-fisted control of his work, distribution, and revenue stream has not caused the demise of Reznor’s livelihood. Trent Reznor is still a rock star.

The result: thousands of remixes and millions of downloads. Relinquishing tight-fisted control of his work, distribution, and revenue stream has not caused the demise of Reznor’s livelihood. Trent Reznor is still a rock star.