What Is Free Culture?

What is free culture?

What is free culture?

Free culture is a growing understanding among artists and audiences that people shouldn’t have to ask permission to copy, share, and use each other’s work; it is also a set of practices that make this philosophy work in the real world.

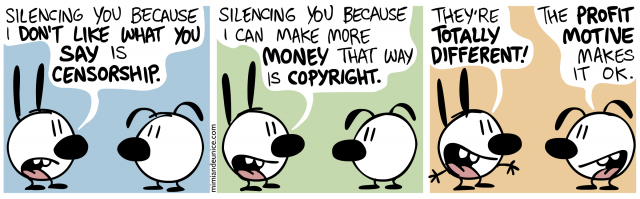

The opposite of “free culture” is “permission culture”, which you probably don’t need to have explained in detail because you’re familiar with it already. In the permission culture, if I write a book and you want to translate it, you have to get my permission first (or, more likely, the permission of my publisher). Similarly, if I wrote a song and you want to use it in your movie, you have to go through a series of steps to get clear permission to do so. Our laws are written such that permission culture is currently the default.

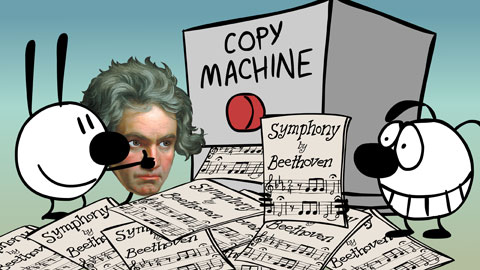

In free culture, you just translate the book, use the song, etc. If I don’t like the translation or the film, I’m free to say so, of course, but I wouldn’t have any power to suppress or alter your works. Of course, free culture goes both ways: I’m also free to put out a modified copy of your movie using a different song, recommend someone else’s translation that I think is better, etc. These are idealized examples, for the sake of illustration, but they give the general idea: freedom takes precedence over commercial monopolies.

There is plenty of free culture out there already. In the past all culture was free culture; in today’s legal environment, the way people create free culture is to put their work out under a free license — a special copyright license that explicitly allows most of the activities that standard copyrights prohibit. Free culture means you can perform it, record it, distribute it, use it in your own works, and anything else. It does not mean you can claim credit for things you didn’t do; that would just be fraud or plagiarism (fortunately, it turns out that allowing works to spread freely is the best way to prevent plagiarism anyway).

Free culture artists make money too. Mostly they do so in the same ways artists always have: direct audience support, commissions, patronage, government and academic support, etc. (Copyright-controlled distribution has never been a major source of funding for art, and wasn’t designed to be.) Free culture artists make a point of working with their audiences instead of against them. They inhabit the Internet as natives, instead of stumbling around in awkward space-suits made of contracts and copyrights and permission forms whose real purpose is to cause enough friction that a corporation has to be paid off to reduce it.

Distilled into a few basic principles, free culture means:

- Artists can use each others’ work without asking permission. If you’re not already convinced that freedom is valuable in itself, read this. Or this. Or this.

- People can receive and transmit art by whatever physical means are available to them. We’ve got an Internet — let’s not be afraid to use it.

- The distinction between audience and artist is fluid, and should remain so because culture is participatory. Free culture means anyone can engage with art and other works of the mind, however they want, without hiring a lawyer first.

- Artists are paid for what they do, not for what other people do. Artists should be paid up front for the work they do. But charging again for music every time a copy is exchanged, for example, is silly. The musicians didn’t do extra work to make more copies, and the copies are transactions between third parties. In the long run, making it harder to share art hurts artists as much as audiences.

- Monopolies hurt everyone except the monopolist. Permission cultures tend to concentrate control in the hands of people who specialize in accumulating control, without doing much to help artists. There’s nothing wrong with running a business that deals with art and artists, of course; the problem isn’t middlemen, it’s monopolies.

One common argument you’ll hear against free culture is that “it should be the artist’s choice” — that if an artist chooses to put their work out under a free license, that’s fine, but they shouldn’t be required to do so. However, this argument is not as convincing as it first seems. When an artist (or, let’s be realistic, a corporation) is given the power to restrict what other people can do with their own copies of things, that takes away everyone else’s choice. When two “choices” oppose each other, we cannot resolve the issue by appealing to choice itself as a value — we have to actually look at which choice is better. Free culture’s answer is that freedom should take precedence; that since no one forces an artist to release their work, once they do release it, it should really be free to spread. Remember, this isn’t about credit: of course artists should be properly credited for their work. But that’s very different from controlling who can see and use the work.

These issues simmered until the Internet came along, and then they really started to boil. Copying became physically so cheap as to be almost costless, and yet the laws against copying only got tighter and tighter, as a frightened industry lobbied for longer copyright terms and more restrictions. This is the dynamic that has given rise to the free culture movement.

(By the way, it was that industry who invented copyright in the first place — in the late 1600s and early 1700s, printers devised it as a replacement for an expiring censorship-based monopoly system. I can’t emphasize that enough: a system designed by business for business is not going to put artists’ interests first, and that’s why it never has. Free culture is not anti-business: there are lots of ways to make money, and if some of those ways involve helping artists and audiences connect, that’s great. In a sense, free culture stands for truly free markets. It is merely against monopolies that force artists and audiences to get permission, usually for a fee and under restrictive terms, to use or access certain works.)

If you’re interested in learning more about free culture, there’s lots of material on this site and elsewhere on the Internet (the Students for Free Culture site is a good resource, though I think it could be clearer on exactly which freedoms are important). There’s an in-depth article here that covers the issues more thoroughly and with more historical context; and here is a good analysis of the harms done by permission culture. If you like what you read about free culture and want to support it, there are lots of things you can do. Whenever possible, support artists directly and by choice, not through intermediaries and under duress. Help sponsor an art project on Kickstarter, and encourage your favorite artists to use direct audience support and release their works under free licenses. Translate, edit, or otherwise contribute to a free cultural work. Release your own works under free licenses. Share this article :-). Spread skepticism whenever you see special pleading, especially in word choice: copying is not “theft”, “filesharing” is really “music sharing”, a copied DVD is not equivalent to a “lost sale”, etc.

Free culture is culture. That’s all it has ever been. The question is simply how much we value freedom.

more than downloading some files without permission, and we were pleased (though not surprised) to see QuestionCopyright.org board member James Jacobs

more than downloading some files without permission, and we were pleased (though not surprised) to see QuestionCopyright.org board member James Jacobs