“Incentive to Create…”

Cross-posted from Mimi & Eunice.

Cross-posted from Mimi & Eunice.

(Translations: Français)

Why don’t books get translated?

If you think it’s because it’s hard to find willing translators, or because the skills required are too rare, I’d like to offer two case studies below that point to another explanation:

The reason translations don’t happen is that we prohibit them. That is to say, translations are what happens naturally, except when copyright restrictions suppress them.

If you’re skeptical, consider the following tale of two authors, one whose books are free to be translated by anyone, another whose books are not.

We’ll even stack the deck a bit. The author whose books are freely translatable will be a relatively minor author, one whose books are not, to be perfectly honest, of earth-shaking importance. Whereas some of the the books by the other author are acknowledged masterpieces in their original language, and you will see quotes from a prominent scholar about how the absence of translations is “one of the great intellectual scandals of our time”.

The first author is me. I’ve written two books, both available under free licenses, and although I’m proud of them and glad I wrote them, neither is of any great historical significance. The first, published in 1999, was a semi-technical manual on how to use some collaboration software. Despite its limited audience and my having put it online in a somewhat cumbersome format, several volunteer translation efforts sprang up quickly, and at least one (into German) was completed. The other efforts may have been completed as well; I’m not sure, and since the book is old now and I can’t read the translations anyway I haven’t bothered to track them down. Note I’m really just talking about the volunteer translations — the ones that people started because they wanted to, without asking anyone’s permission first. There was also a translation into Chinese, which was completed and which I have a paperback copy of, but we won’t count it as evidence here because it went through publisher-controlled channels.

My next book, first published in 2005, likewise appeals to a fairly limited audience: it’s about how to manage collaborative, open source software projects — I wasn’t exactly aiming for the top of the bestseller lists. But with the gracious cooperation of my publisher, O’Reilly Media, I put it online under a free license, this time in a somewhat more amenable format, and volunteer translation efforts sprang up almost immediately. Several of them have completed their translations: the Chinese, Japanese, Galician, German, Dutch, and French. The Spanish is almost done, and there are others still under way that I’m not even bothering to list here.

(Yes, by the way, some of those translations are available in high-quality commercial paper versions, and I have copies of them at home. Commercial activity is perfectly compatible with non-restrictive distribution models, as we have pointed out before.)

So… all this for a book on open source software collaboration? Really? What does this tell us?

Well, let’s look at a contrasting example.

The author Hans Günther Adler (published as “H.G. Adler”) died in 1988 having produced what are widely accepted as some of the core works of Holocaust literature in German. Very few of his works have been translated into English, but recently one, the novel Panorama, was published in English and was widely reviewed.

A look at two of the reviews shows why here at QuestionCopyright.org we consider reframing the public conversation around copyright to be our primary mission. Both reviewers — obviously intelligent, obviously in agreement about Adler’s significance, and writing for two of the most influential literary publications in the English language — comment on the shameful absence of Adler translations in English, yet collapse into a curious kind of passive voice when it comes to the reasons for that absence.

First, Judith Shulevitz in the New York Times:

Every so often, a book shocks you into realizing just how much effort and sheer luck was required to get it into your hands. “Panorama” was the first novel written by H.G. Adler, a German-speaking Jewish intellectual from Prague who survived a labor camp in Bohemia, Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and a particularly hellish underground slave-labor camp called Langenstein, near Buchenwald. Adler wrote the first draft in less than two weeks in 1948… He wound up in England, but couldn’t find anyone willing to publish the book until 1968, 20 years and two drafts later. The book is coming out in English for the first time only now.

It’s hard to fathom why we had to wait so long. … [Adler] is almost entirely unknown in the English-speaking world. Only three of his books have been translated: a historical work, “Jews in Germany”; a novel called “The Journey”; and now, “Panorama.” That American and British readers have had such limited access to Adler’s writing and thought for so long is, as the eminent scholar of modern German literature Peter Demetz has written, “one of the great intellectual scandals of our time.” [emphasis added]

— “A Vanished World. Scenes from the narrator’s past are illuminated in H.G. Adler’s first novel, appearing only now in English.”

by Judith Shulevitz

New York Times Book Review, 30 January 2011

And this from Ruth Franklin writing for the New Yorker:

…Hermann Broch wrote that the book [“Theresienstadt 1941-1945”] would become the standard work on the subject, and that Adler’s “cool and precise method not only grasps all the essential details but manages further to indicate the extent of the horror in an extremely vivid form.” (The book was published in Germany in 1955 and quickly became a touchstone in German Holocaust studies, but it has never been translated into English.) [emphasis added]

— “The Long View: A rediscovered master of Holocaust writing.”

by Ruth Franklin

New Yorker, 31 January 2011

Now, to be fair, Shulevitz and Franklin were writing reviews of Adler’s work itself, not analyses of why those works have been so little translated into English. Yet it is striking that both choose to comment on the absence of translations, at some length, and yet they don’t speculate on the reasons at all. They merely describe the situation and express regret, as though it were bad weather. There is no outrage or frustration at the fact that the reason we don’t have those translations is simply that they have been suppressed before they could be started.

I’m not even going to put qualifiers like “probably” or “likely” before that. It should be treated as a finding of fact, at this point. If my books — my little tomes aimed a small sub-demographic of the software development world — get translated multiple times from English into languages with smaller readerships, then there is simply no way that H.G. Adler’s much more important books, on a much more important topic, would not have been translated from German into English already, if only anyone (or more importantly, any group) who had the ambition to do so had been free to. English and German have a huge overlap in terms of people fluent in both languages, and there is wide interest in Holocaust studies among speakers of both languages. Furthermore, there are non-profit and state funding sources that would have gladly supported the work. That happened even with mine, for example: the Dutch translation was published in book form by SURFnet, who paid the translators to guarantee completion. It would be incomprehensible if funding could be found for that but somehow not for Adler translations.

The fact that the reason for the lack of Adler translations — and the lack of translations for other important works — is not immediately understood by all to be copyright restrictions points a glaring weakness in public debate about copyright. Right now, translators can’t translate if they don’t secure the rights first, and since the default stance of copyright is that you don’t have those rights unless someone explicitly gives them to you, most potential translators give up without even trying. Or more likely, they never even think of trying, because they have become habituated to the permission-based culture. The process of merely tracking down whom to ask for permission is daunting enough, never mind the time-consuming and uncertain negotiations that ensue once you find them.

It is no wonder that so many worthy works remain untranslated, given these obstacles. But it is a wonder that we continue to hide our eyes from the reason why, even as it stares us in the face.

Peter Jaworski is a contributor to the libertarian Canadian blog The Volunteer. In a post reprinted below, he wrestles with the idea of intellectual property, proposals to reform copyright law, and the use of copyleft licenses. We ran across his essay because he draws extensively on the comic strips (and one of the Minute Memes) of Nina Paley, artist-in-residence here at QuestionCopyright.org. Peter’s discussion expresses very well the deliberations of many people who are open to the critiques and proposals advanced on this site but who are, nevertheless, hesitant.

We’re reprinting it here partly to get your reactions. Peter is honest about his emotional response to the idea that someone who puts a lot of effort into their art is entitled to something — reward, or control, or recognition — and this makes him doubt his support for sharing. Interestingly, he reverses the usual position: he says “on most days, I […] think intellectual property is bunk. But I’m open to being persuaded, if you’ve got a good story to tell.” He starts from a pro-sharing stance, but wonders if he’s right. People like Peter are the “independent voters” of the copyright reform movement, if you will, and understanding their instincts is central to our mission. What would you ask Peter?

by Peter Jaworski on November 3, 2010

Mimi and Eunice is a cartoon strip drawn by Nina Paley. Nina does not believe in intellectual property. She lets just anyone reprint her comic strips, provided no one pretends that the work is theirs. That’s the only restriction she views as legitimate — no fraud or attempt to mislead people about the originator of the work.

Nina endorses “copyleft.” Go ahead and click the link for an explanation. For an extended explanation of just what copyleft means, and why Nina is often grumpy, check out her blog post on the branding confusion with Creative Commons licences here.

Here’s a little video she put together highlighting her views on the difference between ordinary theft, and intellectual property “theft”:

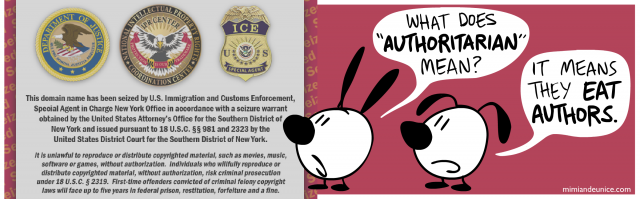

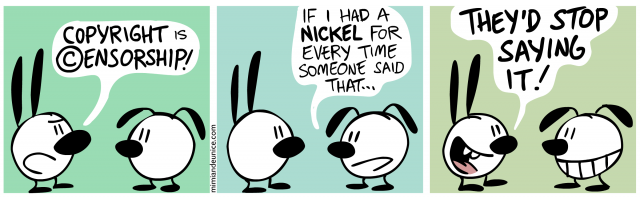

And here are a couple of Nina’s older cartoons that capture some of her attitudes about copyright:

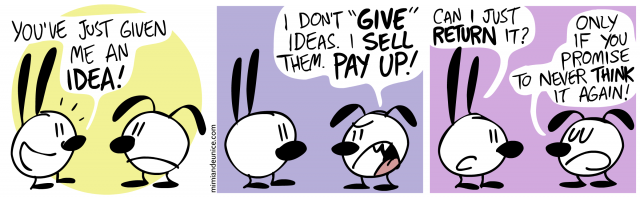

What makes Nina really interesting is that she isn’t opposed to copyright because she’s opposed to the market or to capitalism. Far from it (or so it seems to me). She likes the idea of people making money. Take these as an example:

I’m often unsure about how to view intellectual property. On most days, I agree with Nina. But I’d be curious to hear if anyone has a particularly strong opinion about copyright.

The video highlights an interesting fact about intellectual property “theft” — the first person doesn’t really “lose” anything. When I make a copy of a CD, for example, I haven’t taken away your ability to enjoy that CD. We both get to listen to that CD. And that’s different from me taking your physical property, taking your CD. Now I have the CD, and you don’t. I get to enjoy something that you can no longer enjoy.

I’m aware of the argument that copyright protection promotes new ideas, and promotes investment in things like music and movies and so on. On its face, that’s pretty persuasive, if it’s true. I don’t want there to be less music and fewer Disney cartoons. I want more music, more cartoons, more books, and more movies. If I’m going to spend a lot of my time writing a book, I’d like to be compensated financially. If there were no copyright protection, the first idiot with a bit torrent client can just take my work and no one would ever have to pay me for all the work that I’ve put into making the song, the movie, the book, the idea.

One counter to that argument is the “first-mover advantage” claim made by economists. The first entrant into a market has a surprisingly strong benefit, for many possible reasons. If you come up with an idea, you can be the first mover. That may be sufficient to motivate the making of just the same amount of thinking-based stuff. Maybe. Then the argument from outcomes would be overcome by appeal to what would happen without copyright.

When it comes to music and movies, I tend to think that what needs changing is the method of making money, not the enforcement of copyright protections. If we’re honest with each other, we can admit that we already operate on a system where people volunteer to pay for music. You don’t have to pay for music any more. Music is too readily available on the internet, and no amount of resources thrown at enforcement will end the torrent of, well, torrents.

In my mind, artists should view their music as reason for people to go to their concerts and buy their merchandise. They get paid for concerts, not for the music. The music is what entices the consumer to go to concerts.

Maybe.

I have friends in the music industry. Lindy Vopnfjord, in particular. I know how much work he puts into his music. I know that he should be, if the world were just and aware of what is good, rich as bananas. I still remember the first time I listened to his CD, Suspension of Disbelief, on a drive to Waterloo with my sister. I was like, “who’s this?” and she was like, “that’s my friend Lindy,” and I was like, “oh my God, this is going to be a disaster. But I’ll just be polite, swallow hard, and listen nicely.”

I listened nicely. And then I insisted we play the CD over again. And then again, for a third time. And then I was shocked that my sister knew this guy, and then I insisted that she introduce me.

True story.

Now Lindy and I are good pals and chums, and he fills me in on what’s happening in the Toronto music scene, as well as how musicians try to make money. It’s not easy. And I can understand how I’d feel if I spent all this time writing lyrics, putting together a melody, etc., and some douche sitting behind a computer clicked some keys and, voila, all my work is right there available for anyone and everyone to take and listen to without having to give me a shiny dime. All those pleasant moments punctuated by Beautifully Undone (one of Lindy’s songs), and no benefit accrues to the artist. Seems unfair.

Still, like I said, on most days, I agree with Nina, and think intellectual property is bunk. But I’m open to being persuaded, if you’ve got a good story to tell. I’m all ears.

Addendum: The argument from effort above, if we can call it that, gets real short shrift from Nina. She has a running gag that makes use of poop as the central artefact to mock intellectual property. Here’s that series:

(P.S., you don’t have to pay me for writing all of this, even if you liked it. It took me a while to get all the links for you, and to embed all those videos, and to think about the story I’ll tell you, and how to construct the argument or two that I’ve included in this post. You can’t claim that you wrote it, not that I’m suggesting that you would. But here it is, free for you to look at, read, excerpt and otherwise make use of. It’s interesting to note the proliferation of blogs — essentially free content — that exists out there in cyber-inter-web-world with something approaching zero per cent of bloggers making money off of blogging. But just look at all the content that is produced! Is it really true that, without copyright protection, we’d have less intellectual property? Blogs make me think there wouldn’t be less…)

Calling all law students — or at least the ones who weren’t planning to work for the RIAA later:

Our legal intern position is open! We’re looking for someone interested in learning more about copyright law and using it to promote freedom. Several of our projects have legal components, so the responsibilities of the position are varied. They will involve research in U.S. and international copyright law, non-profit law (federal and CA state), some trademark law, tracking legislative developments, some writing, etc. The minimum time commitment is about five hours a week, with more available if you want it. A New York City location is preferred but not required. There may be some limited travel (which we pay for), at your discretion.

The position is unpaid, but you would be working with an experienced lawyer (our counsel, Karen Sandler), and we’re happy to meet reasonable requirements for law school credit.

Interested? Contact us. We’ll keep the posting open until we get the right candidate — it could be you!

We’re very pleased to announce a $10,000 grant from the Kahle/Austin Foundation, received in the first few days of 2011!

Our team is still considering how best to allocate this New Year’s gift, but it will likely be divided between projects and fundraising (turns out it costs money to raise money, and we were right in the middle of a grantwriting effort, so this is perfect timing).

If you like our work, please consider joining Kahle/Austin in supporting us. We are a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, so donations are tax-deductible in the U.S. Your support means we can make more Minute Memes, help other artists try out the freedom-friendly audience-distribution model used so successfully by our Artist-in-Residence Nina Paley, and do many other things to help make the world safe for sharing again.

Many thanks to the Kahle/Austin Foundation, and to our board member Brewster Kahle.

On January 1st, Rick Falkvinge, the founder of the Swedish Pirate Party and its leader for the past five years, stepped down, and Anna Troberg took over the reins.

This is significant for a few reasons. The Swedish Pirate Party is clearly here to stay — having won seats (yes, that’s plural, “seats”) in the European Parliament, they are now concentrating on in-country elections. The leadership transition is a sign of stability: Falkvinge recognized that what the party needed now was an organization builder with new ideas, felt he’d done his best work in founding the Party and leading it to its first victories, and moved on. By all accounts Anna Troberg is exactly the right person for the job.

Rick Falkvinge will now be able to concentrate on political evangelism full time at his English-language site: Falkvinge on Infopolicy. In his words:

“…I feel there has been a language barrier from the Swedish discussion, which is several years ahead, to the rest of the world. I want to bridge that.”

This is welcome news, because here in the U.S. we need more of what might be called the “Swedish School” of copyright reform.

To the extent that copyright debate here has moved in a positive direction at all, it’s been largely through the rhetoric of artistic freedom, so-called “fair use”, and worries about gigantic conglomerates holding cultural monopolies. Those are important concerns, but there’s another aspect that doesn’t get enough attention: strong copyright enforcement inherently means weak civil rights, because to enforce copyright restrictions in an age of networked computers means someone must watch what everyone’s downloading. This is what Nina Paley was getting at in her Copyright and Surveillance Minute Meme for the EFF, and it’s been a major part of the Swedish Pirate Party’s platform since day one — in fact it’s essentially why the party was founded in the first place.

We helped Falkvinge bring that message here on his U.S. West Coast tour in 2007, and it’s only become more important since then. Consider that in the name of enforcing publishers’ monopoly rights, Amazon had to keep track of what its customers were reading in order to erase books from customer’s e-book readers in 2009. That’s not an exceptional case, it’s a structural inevitability: in the digital age, content monopoly means user surveillance. How else could it be? There is no other way to enforce the monopoly. If you don’t want that world either, help us keep a better one.

We’ve got Falkvinge on Infopolicy in our right sidebar now. We hope you’ll watch the site, as we will be. And if Rick Falkvinge says something that strikes you as overly worried today, please make a note of it, wait a couple of years, and see how it looks then. Chances are he’s just a little bit ahead… as he was when he founded the Swedish Pirate Party.

We’ve got a new tool for questioning copyright, and we hope you’ll use it too.

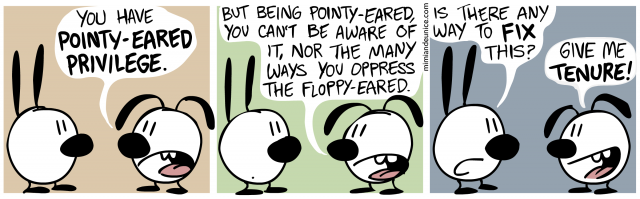

Our Artist-in-Residence, Nina Paley, recently started her new online comic strip Mimi & Eunice. Mimi & Eunice is about a lot of things, but one of them is copyright — how it gets between artists and their audiences on the Internet, how it can stifle creativity, how it’s increasingly being used as part of broader censorship efforts, etc.

The strips themselves are, of course, released under a free license, and display a fully Internet-compatible copying notice:

♥ Copying is an act of love. Please copy & share.

Each of the strips on copyright is designed to be a little comment bomb that you can drop into a post or a discussion to help make a point. People have already started doing so, for example at Techdirt and other places, and it’s been great watching them spring up around the Internet. We invite you to join in! Some things are just easier to say with a strip:

…and there are many more to browse over at the Mimi and Eunice home site. Use them as you see fit. Each strip comes with clear embed instructions, so it’s easy to include in a web page or an online comment.

Like the Minute Memes, they are rhetorical tools, meant to help make familiar points more memorable. There are certainly times and places where it’s appropriate to point out, calmly and rationally, how copyright term extensions make no logical sense and are a theft from the public domain — but there are also times where it’s just better said with a strip:

A great way to enjoy the comics, and support the artist, is to buy a (signed!) copy of the first book, Misinformation Wants to be Free:

Far be it from us to encourage the crass commercialism of what is to many still a religious season, but if you are for some reason buying gifts this time of year, Misinformation Wants to be Free is an eminently reasonable $20 US, and is sure to be a delightful surprise to discerning readers. The strips are not only about copyright:

Enjoy — and spread the word!

This holiday weekend, the US Department of Homeland Security seized more than 70 web sites – while sites like arstechnica.com and techdirt were on vacation, and the mainstream media were devoted to stories about holiday shopping.

![]() Over at Techdirt, Mike Masnick is naming names. We’re reposting his list below, but please visit his original article. (Techdirt is great on most of the issues we care about – I read it daily.)

Over at Techdirt, Mike Masnick is naming names. We’re reposting his list below, but please visit his original article. (Techdirt is great on most of the issues we care about – I read it daily.)

The 19 Senators Who Voted To Censor The Internet:

- Patrick J. Leahy — Vermont

- Herb Kohl — Wisconsin

- Jeff Sessions — Alabama

- Dianne Feinstein — California

- Orrin G. Hatch — Utah

- Russ Feingold — Wisconsin

- Chuck Grassley — Iowa

- Arlen Specter — Pennsylvania

- Jon Kyl — Arizona

- Chuck Schumer — New York

- Lindsey Graham — South Carolina

- Dick Durbin — Illinois

- John Cornyn — Texas

- Benjamin L. Cardin — Maryland

- Tom Coburn — Oklahoma

- Sheldon Whitehouse — Rhode Island

- Amy Klobuchar — Minnesota

- Al Franken — Minnesota

- Chris Coons — Delaware

Free Speech and Internet Freedom are areas where party affiliations are meaningless. Some of the worst enablers of censorship are Democrats; some of the strongest advocates for liberty are Republicans. Conservative bloggers created DontCensorTheNet.com, which I just lent my support to; meanwhile everyone’s favorite liberal, Al Franken, voted in favor of drastic censorship this morning. Please pay attention to what the people you elected are doing!

COICA stands for “Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act.” Once again the word “counterfeits” is completely misused: this act has nothing to do with real counterfeiting. The EFF states:

The main mechanism of the bill is to interfere with the Internet’s domain name system (DNS), which translates names like “www.eff.org” or “www.nytimes.com” into the IP addresses that computers use to communicate. The bill creates a blacklist of censored domains; the Attorney General can ask a court to place any website on the blacklist if infringement is “central” to the purpose of the site.

If this bill passes, the list of targets could conceivably include hosting websites such as Dropbox, MediaFire and Rapidshare; MP3 blogs and mashup/remix music sites like SoundCloud, MashupTown and Hype Machine ; and sites that discuss and make the controversial political and intellectual case for piracy, like pirate-party.us, p2pnet, InfoAnarchy, Slyck and ZeroPaid . Indeed, had this bill been passed five or ten years ago, YouTube might not exist today. In other words, the collateral damage from this legislation would be enormous. (Why would all these sites be targets?)

COICA also stands for Censorship Of Internet Communications Act. The acronym is easy to remember because it sounds like CLOACA, with which it shares many similarities.

Some numbers and slides from the Sita Distribution Report (crossposted from ninapaley.com):

Q. Who owns culture?

Q. Who owns culture?

A:

Q. How do you make money?

A:

Q. How many people have seen Sita Sings the Blues?

A. I can’t know for sure, but as of today it’s been downloaded 258,744 times from archive.org, viewed 403,421 times at youtube (full movie) plus another 183,649 (installments); it’s been shared widely via torrents, screened at festivals and cinemas and libraries and classrooms, and otherwise copied all over the world. Googling “Sita Sings the Blues” today yields about 2,620,000 results. Sitasingstheblues.com enjoys about 193,000 visits a month.

Q. How much have you received in donations so far?

A. About $50,000.

Q. How much have you received in profits from the Sita Merchandise Empire?

A. About $45,000 for me as of March 2010. The store opened in March 2009, so that represents one year’s income. The store grossed about $83,000 during that time.

Q. How much have you made from theatrical screenings?

A. About $9,000 for me. I estimate box office gross was about 8x that much, or approx. $72,000, but that’s a gross estimate.

Q. How much have you made from other DVD distributors?

A. About $6,000 so far, which represents a small portion of gross DVD sales from other distributors. Our own DVDs which we offer at the Sita Merchandise Empire are accounted as store income, above.

Q. How much have you made from broadcast?

A. Only about $4,000 so far. Most broadcasters’ legal departments can’t wrap their heads around an open licensed movie. Happily New York’s PBS Affiliate Channel 13 embraced it, as did Link TV. Broadcasters, please show the movie!

Q. How much have you received from voluntary payments from cinemas and festivals?

A. About $12,000. I don’t use copyright to compel payments, but many venues share revenue of out decency and a mission to support artists, rather than legal threats.

Q. What other income have you gotten from the film?

A. Amazingly, $12,500 in Awards money. It still boggles my mind.

Q. So how much money did you personally make releasing a Free film under an open ShareAlike license?

A. In the film’s first year, I got about $132,000. I’ve received more since then.

Q. How much did the movie cost you to make?

A. $270,000: a $200,000 budget plus $50,000 to license the old songs via a “step deal” sufficient to decriminalize it for Free sharing, and another $20,000 in bargain-basement legal transaction costs. So I’m not in the black yet, but I am no longer in personal debt.

Q. How much would you have made had the movie not been Free?

A. When I was still trying to sell conventional monopoly rights to distributors in 2008, the highest advance I was offered was $20,000; I was told by one reputable distributor that the most I could expect in my wildest dreams to make in a 10-year contract was $50,000, and more realistically I could expect about $25,000.

Watch the video:

Nina Paley at HOPE 2010 – entire talk from Nina Paley on Vimeo.