The “Creator Endorsed” concept is a very robust way of monetizing creative works, and can be adapted to many different strategies. Here, I want to suggest an advertising-based model which resembles syndicated television.

Free culture videos could use an advertising model enabled by the Creator Endorsed mark, based on the same business models as have been used for decades for syndicated television.

With syndicated television (e.g. “Star Trek: The Next Generation”) it was common to sell advertising on the syndication tape as well as to leave spots for local ads (this was one of the primary revenue sources for the studio). The local station would pay for the syndication tape, agreeing, among other things, to leave the syndication ads on the tape when playing the show, and possibly adding their own ads.

Personally, I think if one sold a 30-second to one-minute spot in a 30-minute show, no one would even bother to edit it out unless it was a really irritating ad — even without there being any repercussions to doing so. Furthermore, many viewers accept a “reasonable” level of ads as a positive thing, since they know they help pay for the show, and especially if the ads are well-targeted (for example, although I skip DVD advertisements on subsequent viewings, I frequently watch them on the first viewing out of curiosity for what’s being advertised).

Today, with internet distribution, it’s fairly common to put “wrap” ads on the beginning or end of a video, advertising the distributor or sold by the distributor, but it’s rare to put them into the middle of it. Either style will work for the model I’m describing here.

If we are to sell advertisements, however, the advertisers will want some kind of guarantee that their ads will be seen. This is the main reason this model has not been previously used for free culture videos, and so it’s the problem we have to solve

Why not just rely on the Creative Commons’ “Attribution” Clause?

The most common licenses for free culture works are of course, those promoted by the Creative Commons. Two particular licenses, the Creative Commons Attribution and Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike are widely regarded as “free” licenses, and are the most widely used choices for free media.

All six of the core Creative Commons licenses start with the “Attribution” (By) module. This gives a partial, but not complete, solution to the problem of retaining advertisements.

Attribution is not quite as simple as it sounds, because it’s not always clear exactly who is the principle “creator” of a work (especially for larger, more collaborative works). For a film, the correct “attribution” might be understood simply to be the studio name or it might be interpreted to mean the entire credits roll at the end of the film.

It is actually up to the copyright owner to decide which of these is acceptable, so conscientious users of the license will specify what they expect.

Naively, you might think that this alone is sufficient to insist on advertisements, but this is not the case.

The detailed wording of the licenses is much more specific about what must be included, and it does not require anything to be included verbatim. Instead it simply says that notices “may be implemented in any reasonable manner.” It also specifically indicates what types of information must be kept:

- “the name of the Original Author” or if provided, a pseudonym or the name of other “Attribution Parties”: “(e.g., a sponsor institute, publishing entity, journal)”

- “the title of the Work if supplied”

- “the URI, if any, that Licensor specifies” provided that the document at the URI specifies “the copyright notice or licensing information for the Work”

- “a credit identifying the use of the Work in the Adaptation” (for adaptations only, of course, as opposed to verbatim copies)

In general, the Creative Commons “Attribution” clause has not been considered to include advertisements or sponsorship notices. However, you can insist on mentioning sponsors and legal notices in the credits. Even this kind of representation has some value (similar to sponsorship credits as used with Public Broadcasting).

In fact, although it’s perhaps early to call it a “convention”, the times I’ve seen a CC license used on a film or video, the attribution requirement for copying the whole film has been to “roll the entire credits”, which frequently does include sponsorship notices of some kind (e.g. the “Blender Foundation” is acknowledged in the Blender Open Movies). A much shorter attribution is usually specified for works which merely copy or remix the video (again referencing the Blender Open Movies, this credit is simply “Blender Foundation | www.blender.org”).

Enter the Creator Endorsed Mark

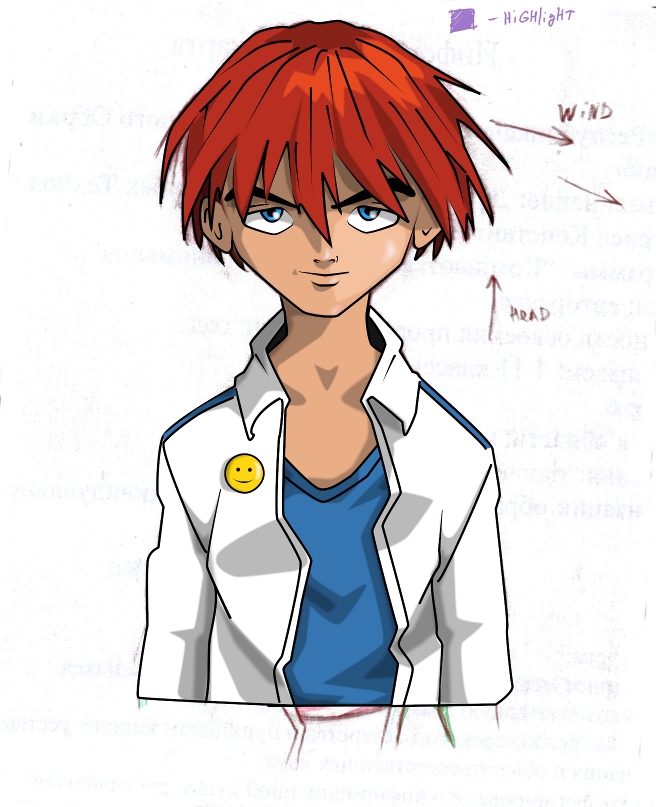

The “Creator Endorsed” mark, however, with its trademark protection allows a more direct requirement, however. A simple title block along the lines of this:

Titlecard for endorsement with notices about the advertising and how to license endorsement for variations (The text font is Dream Orphans, a free-licensed font included in Debian GNU/Linux. The URL is scaled “Courier 10-point”). The aspect ratio is for HDTV format (16:9). Obviously many variations are possible. I use a blue background to symbolize loyalty (though this is closer to indigo). Be sure to change the URL if you use this image!

This mark would be restricted to copies which carried the commercial break, just as with syndicated television. As part of the distribution terms, any removal of ads (as well as any other edit of the piece) would require removal of this CE mark unless permission was explicitly acquired (which is simply demanding truth in advertising — clearly if there are no commercials or the commercials are different, they do not benefit the artists and the mark would therefore be an improper use of the trademark).

It might be worth noting that the Creative Commons licenses specifically acknowledge this kind of separate endorsement agreement.

Of course, people could still exercise their right of modified distribution under a Creative Commons license. This would include the case of simply stripping out the advertisements — provided they also remove the CE mark. But really, who’s going to do that? Retaining the endorsement mark (and the ads) has a definite goodwill value to the distributor at little to no cost (provided the ads are not onerously long or disruptive to the work).

Also, while the advertisement could be legally stripped out, notices included in the video credits would not be. And it would be possible to include an educational notice indicating that official releases contain the “Creator Endorsed” mark, along with a link for additional information (this is probably covered by the legal-notices). Also, if you follow usual film conventions, cutting out the credits would also mean cutting out the end credits music, which is another disincentive to doing it.

What this creates is a revenue model very similar to syndicated television, with most of the same players. However, the copyright regulation is replaced by the simple signaling mechanism of the “creator endorsed” mark.

Fan Remixes

Another value to this endorsement mark would be that it would establish the “canonicity” of the video — distinguishing it from “fan fiction” remixes.

Fans, of course, would be entitled to remix and adapt the work to their hearts’ content. The only requirement would be that they must remove the endorsement mark. As a positive nod to such remixes, it might even be fun to provide (on your release site, pointed to by the URI in the credits) an alternative title-card for fan remixes. Using it would be entirely voluntary, of course, but it might catch on as a fan-to-fan signal:

Fan remix titlecard designed to fit in the same place as the endorsement titlecard, but clearly distinguishable. I use green to symbolize total freedom, as use of this card is voluntary and places no requirements at all on the work.

The Aesthetics of Advertising

For some, of course, the idea of “polluting” their work with advertisements is appalling. You might think, “Isn’t this why I’m doing free culture — so I don’t have to resort to such crass commercialism?” Well, if you feel that way, this is probably not for you!

However, free culture artists have the same sustainability concerns as anyone else, and this is another potential revenue stream. Also, we do have a number of video formats in which advertisements have already become part of the landscape. In television series, for example, it’s common to use commercial breaks as natural punctuation to the story, separating the acts. There are also artistic elements such as the five to ten second “eye catch” animations that are used in anime productions to delimit the commercials. These are so much a part of Japanese animation that they are included even in most direct-to-video releases of Japanese anime (“OVAs”), even though there are no commercials between them.

There’s obviously a higher premium on having good quality ads: memorable, well-targeted, and if possible, topical to the show. If they are the right ads, your audience will want to see them. So the challenge will be to hold the ads up to that standard, and the voluntary nature of the medium naturally encourages that.

Can We Actually Sell These Ads?

This is a tougher question, and I’m no advertising executive, so I can’t really answer it myself (though I would love to discuss this with someone in the business of selling commercial advertising).

I can observe, however, that advertisers have generally been eager to join the bandwagon on any opportunity that has become available, even if it does take them a little time. I remember when the idea of an advertisement on an internet website was just as bizarre a concept — and look at us now.

So the problem is really a conventional start-up problem. How to get the ball rolling? The biggest questions at the outset are:

- Will (re-)distributors actually leave the ads in?

- Will fans prefer the official releases or stripped ones?

- Will advertisers believe enough in the system to pay reasonable advertising rates for inclusion?

- Will any advertising agency work with free culture video producers to sell this kind of advertising?

Each of these represents a small leap of faith: the ad agency has to believe advertisers will bite; advertisers will have to trust the fans; and fans will have to support those sites that keep the ads.

One argument in favor is that this isn’t really very different from the situation with existing copyright-enforced ads, because copyright enforcement on that level is nearly impossible. So in practice, it’s more of a voluntary system too. There are already many television shows copied onto YouTube and other places with the ads stripped.

But copyright doesn’t have the effect of making only these stripped versions illegal. It makes videos with ads just as illegal. So there’s actually no incentive for posters to leave the ads in.

With an endorsement model, there is. Leave the ads in, and you get the filmmakers’ blessing! Far from rebelling, fans are likely to revel in that kind of freedom. So everybody wins: the artist, the advertisers, and the fans.