|

|

|

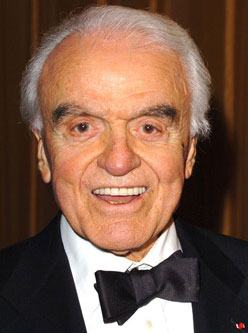

Jack Valenti: “We are facing a very new and a very troubling assault on our fiscal security, on our very economic life and we are facing it from a thing called the video cassette recorder and its necessary companion called the blank tape.” [1]

|

E. N. Elliott: “(W)itness…the existence of the ‘underground railroad,’ and of a party in the North organized for the express purpose of robbing the citizens of the Southern States of their property….” [2]

|

Why do discussions of Free Culture trigger such strong emotional response?

People hold very strongly to ideas about the meaning of property. Jill Lepore, in a New Yorker Article called “The Politics of Death” (Nov. 30, 2009, p. 62) writes:

life, liberty, and property are the rights that Americans talk about, and fight over….Taking a long view of American history, it’s possible to argue that each of these rights has led to a fracture in the body politic, a dispute in which there seemed no room for compromise. …a swirl of disputed ideas have gathered around each of these contested rights. But, from one era to the next, the ideas have been different.

Lepore’s article concerns itself primarily with “life” politics: “…in the past half century, Americans have been fighting over the right to life.” But immediately prior to that statement lies this rich, enlightening paragraph about historic changes in Americans’ ideas about property:

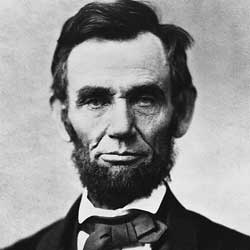

In the nineteenth century, Americans worried about a conspiracy against property — a property interest in people. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise, which prohibited “this species of property” north of the thirty-sixth parallel, divided the country in half. Jefferson called it a national “act of suicide.” Four years after the Compromise of 1850 redrew the line between slave and free states, Abraham Lincoln wrote that the framers had forborne “to so much as mention the word ‘slave’ or ‘slavery’,” which left the disease festering in the body politic….in 1857, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court ruled that the framers had intended to define the “negro race” not as people, but as property, to be “bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise.” Slave owners feared an abolitionist conspiracy, “a party in the North organized for the express purpose of robbing the citizens of the Southern States of their property.” In 1859, John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry realized those fears. On the floor of the Senate, Jefferson Davis made a threat: “If we are not to be protected in our property and sovereignty, we…will dissever the ties that bind us together, even if it rushes us into a sea of blood.” The following year, South Carolina became the first state to secede, citing as its reason the federal government’s failure to honor its “right of property in slaves.” The contested right to property led to the Civil War, and six hundred thousand dead.

Discussions of Intellectual Freedom and Intellectual Property dance around this cherished American right: property. (That said, the term “Intellectual Property” came into use only recently; the term was not used at all when the US Constitution was written.) Property is sacred. Ideas about property change slowly, violently, and fundamentally. Today we find slavery so morally abhorrent, it’s hard to believe that human property was a common, socially accepted institution less than 200 years ago. Property rights — even in human beings — were sacrosanct. People will fight to the death over not just property, but ideas about what property means.

Anything that challenges definitions of property can provoke heated, emotional responses — even from people with no direct stake in the property in question. I own no real estate, and probably never will, but like many I was outraged by Kelo v. City of New London, Connecticut:

“In Kelo, the Court said New London could take private property through eminent domain for the development of a hotel and convention center.”

To me and many others, it appeared the Government was undermining a fundamental “right to property.” Even as a non-property-owner, I care about what property means.

And so, statements like “Copying Is Not Theft” trigger an emotional response, even from those with no direct stake in Intellectual Property. Redefining property undermines social stability and can lead to widespread violence. Most people will tolerate certain unpalatable definitions of property (that human beings can be property in the case of slavery, or that culture and ideas can be property in the case of IP) in exchange for social stability, because social stability underlies everyone’s security.

But don’t tell that to a slave.

I hear this a lot:

“IP is problematic, but the decision to free works should be the artist’s choice.” [3]

Legally artists DO have the right to choose whether to release works freely or place copyright restrictions on them. So we don’t need to discuss “should.” The nice response is to say, “yes they have that choice, and therefore I wish to present arguments in favor of choosing freedom.” Which I do.

But I can’t help imagining this argument in the early 1800’s:

“Slavery is problematic, but the decision to free slaves should be the slaveholder’s choice.”

As long as the discussion is about “owner’s choice,” we don’t have to question how we define property.

Free Culture activists fastidiously avoid the “s-word”, even though the similarities are obvious and many, because invoking these comparisons triggers such high emotions that rational discourse becomes even less likely. And yet… “those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.” We stand to learn more about today’s struggles over “Intellectual Property” by studying historical struggles with human property. Because my audience is more level-headed than average, I’m going to explore some of these similarities here.

But first, let me clear out of the way the big difference between Intellectual Property and Slavery: cultural works aren’t people, and don’t have human feelings or rights. Owned cultural works aren’t comparable to human slaves. The argument against Intellectual Property is not that it enslaves works, but that it enslaves thinkers — audiences, artists, and all participants in culture (except the “owners,” who are harmed in other ways).

Now for the similarities:

Moral arguments

Moral arguments against slavery had been around as long as slavery itself. Although slavery diminished in the North primarily due to economic reasons, the US Abolition Movement was rooted in moral argument.

Likewise, moral arguments against patents and copyright have been around since the advent of those institutions. In 1813 Thomas Jefferson argued eloquently against what we today call “Intellectual Property”:

It would be curious then, if an idea, the fugitive fermentation of an individual brain, could, of natural right, be claimed in exclusive and stable property. If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it.

Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation.

In 1841, speaking to the House of Commons, British poet Thomas Babbington Macaulay argued against extending copyright terms:

…even if I believed in a natural right of property, independent of utility and anterior to legislation, I should still deny that this right could survive the original proprietor.

I believe, Sir, that I may safely take it for granted that the effect of monopoly generally is to make articles scarce, to make them dear, and to make them bad.

It’s a great essay, just as relevant today in its moral arguments.

Its economic arguments are less relevant, as it was written 150 years before the Internet. Macaulay could only conceive of “two ways in which (authors) can be remunerated. One of those ways is patronage; the other is copyright.”

He went on to dismiss patronage:

I can conceive no system more fatal to the integrity and independence of literary men than one under which they should be taught to look for their daily bread to the favour of ministers and nobles. I can conceive no system more certain to turn those minds which are formed by nature to be the blessings and ornaments of our species into public scandals and pests.

Ironically, copyright has led to exactly the same problems as the patronage system he described. The modern “minsters and nobles” are media executives. Copyright, instead of curing the evils of the patronage system, grew to reinforce them.

We have, then, only one resource left. We must betake ourselves to copyright, be the inconveniences of copyright what they may. Those inconveniences, in truth, are neither few nor small. Copyright is monopoly, and produces all the effects which the general voice of mankind attributes to monopoly.

If only he knew! All the vices of monopoly, plus the vices of patronage too.

Technological and Economic Changes

Today the Internet offers a third option: micropatronage, the ability of masses of fans to support artists directly. It relies on no monopolies, and fulfills democratic ideals that old patronage and copyright never could.

In the pre-bellum North, mechanical industrialization, especially of agriculture, reduced the economic incentive for slaveholding. Immigrant labor also changed the Northern economy, making slave systems less profitable. Northerners didn’t abandon slavery because they were morally superior to Southerners, but because of economic and technological changes.

Just as farm machinery lowered costs and increased efficiency in agriculture, digital devices have lowered costs and increased efficiency in production and distribution of cultural works. Musicians, artists and authors are beginning to discover their works are more profitable shared through the internet, than distributed centrally. A few economists are pointing out that free sharing of cultural works increases profitability for artists and overall wealth. They avoid moral arguments, focusing on rational market incentives. [4]

Resistance to Control

Most histories of American slavery explore changes in white attitudes. But black slaves always struggled for freedom, regardless of white political trends.

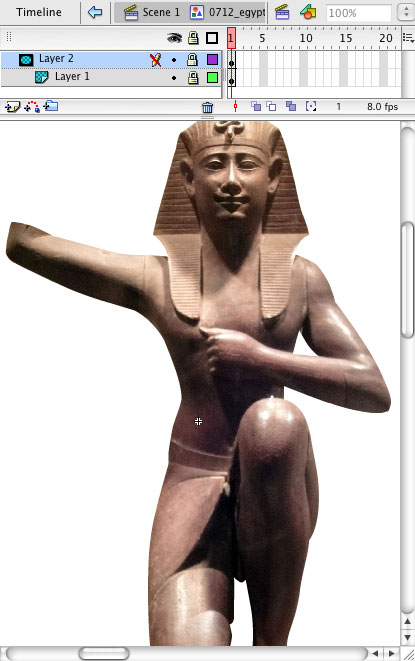

Today we argue whether “Information wants to be free.” Unlike human beings, information lacks feelings and agency. But both human property and Intellectual Property tend to resist control. Slaves somehow got through fences and borders, in spite of property laws. Modern IP owners express the same shock and indignation as pre-bellum slaveholders when their work “gets out.”

|

|

|

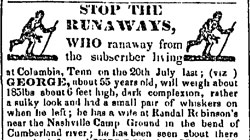

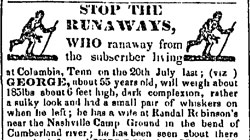

Assisting in the liberation of human property was a Federal crime.

|

Unauthorized sharing of “Intellectual Property” is a Federal crime.

|

Underground Railroad and “Pirates”

“The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th century Black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists who were sympathetic to their cause. [5] The term is also applied to the abolitionists who aided the fugitives.” [6]

Under the Dred Scott decision, “liberating” slaves was illegal. From today’s point of view, the Underground Railroad didn’t “steal property,” but from a slaveholder’s perspective there was no distinction.

Today we have file-sharers, copyists, and copyright infringers, all generally termed “pirates.” There is a moral incentive to “liberate” cultural works through digital sharing [4], but to IP owners this is simply stealing property. Punishment for assisting the “liberation” of IP is severe, just as punishment for aiding fugitive slaves was.

Increasing Penalties

…the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793…made it a federal crime to help a runaway slave.

Punishment in the North for white people and free blacks who assisted in escapes was originally not as harsh — typically a fine for the loss of “property” and a short jail sentence that might not be enforced. But in 1850, penalties became much steeper and included more jail time. Whites who armed slaves, which was often necessary along the dangerous route, could be executed. In the South, anyone — white or black — who assisted a fugitive could face death.[7]

Likewise, punishments for unauthorized copying have grown increasingly severe. In some places, such as France, there are “three strikes” laws that would shut off a person’s Internet access if they are caught illegally sharing three times. In the United States, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 increased the penalties for copyright violation when the violation takes place on the Internet.

Arbitrary Grab-Back

Like copyrights, title to slaves and their descendants were heritable to slaveholder’s descendants:

Oney Judge was interviewed by Rev. Benjamin Chase, and he published the account in a “Letter to the editor” in The Liberator of January 1, 1847. He discussed the fact she could be seized at any time, even 50 years later if Martha Washington’s descendants decided to make a legal claim.

Today, we have countless stories of authors’ descendants claiming copyright infringement, such as Martin Luther King’s kids [8].

Proliferation & Control

As slaves proliferated, their sheer numbers made them more difficult to control. Although all slave rebellions that took place on American soil were suppressed, they required enormous manpower and force to do so. Keeping human property grew increasingly expensive. Meanwhile, the more slaves proliferated, the less the problems of slavery could be ignored. The Government had to become increasingly involved with writing and enforcing slave laws — laws that benefited the few slaveholders at the expense of the many citizens. An ordinary citizen might be willing to ignore his neighbor’s keeping of slaves, until it cost him money.

Today we see a proliferation of information. More cultural works are circulating than ever before. Copyright was much more manageable when there were few authors and fewer printing presses. Today almost everyone is an author, and digital “printing presses” — computers — abound. All that information is hard to control, and the more it proliferates, the more expensive copyright becomes. IP owners must buy congressmen to write ever-more draconian copyright laws, and get taxpayer money to enforce them. As the enforcement of irrational laws sucks up ever more public resources, the public may start to wonder whether the cost of “owning” is worth it.

Big Cotton / Big Content

The big stakeholders in slavery were large plantation owners. Small farmers and industrialists had little use for it, which is why slavery was abandoned earlier in the North. In the South, “…slave ownership was becoming concentrated in fewer hands. Whereas a third of southern whites owned slaves in 1850, a decade later the proportion had dropped to one-quarter. “The American Cotton Industry relied almost exclusively on slave labor, and much of the world’s commerce relied on American Cotton [9]. Hence an 1860 pro-slavery essay collection was backed by Cotton interests and titled “Cotton Is King”.

Today, as Big Media corporations merge, IP is increasingly concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer “owners.” Like Big Cotton before it, Big Content supplies most of our pro-IP propaganda, as well as legislation. [10]

Burden of Documentation

The laws of slave states assumed all black people were slaves. You didn’t need documentation to prove you were a slave; you needed it to prove you were not.

Likewise, modern US copyright law assumes all cultural works are property. Copyright registration is optional; all works are property by default. It is free cultural works that require documentation, not copyrighted ones. All cultural works require extensive documentation to move through mainstream distribution channels; it is never, ever assumed they are free. Cultural works without documentation are called “Orphaned Works,” and not free; great effort is devoted to finding their “rightful owners.”

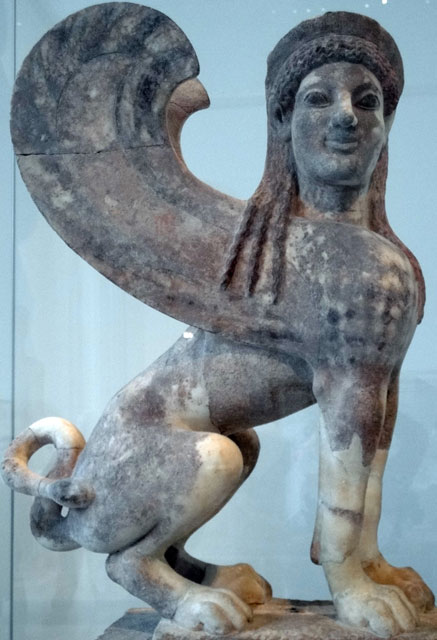

Political Movements

|

|

|

“…a party in the North organized for the express purpose of robbing the citizens of the Southern States of their property…” The Republican Party was founded in 1854 by American anti-slavery activists and modernizers, and first came to power with Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860.[12]

|

“…a party in the North…” Sweden’s Pirate Party was founded in 2006 by Swedish copyright reform activists, and first came to power in the 2009 European Parliament elections, winning two seats.[13]

|

Rhetoric:

“Protection”

According to E. N. Elliott, in his introduction to “Cotton Is King and The Pro-Slavery Arguments” (1860): “Slavery is the duty and obligation of the slave to labor for the mutual benefit of both master and slave, under a warrant to the slave of protection, and a comfortable subsistence, under all circumstances.”

Slavery “protected” slaves. (From what? Other, less kindly slave owners?) In this way, slave owners provided a benefit to the humans they owned, taking care of them. This implied that human slaves couldn’t survive or thrive without being owned.

Likewise IP is called “protection.” Record labels claim to protect and nurture “their” artists. Cultural works are considered helpless without distributors and publishers to “manage” their rights. Corporations that own monopoly rights to artists’ output portray themselves as nurturing, protecting, and necessary.

“Property” vs. “Rights”

Owning human beings and ideas is hard to defend; owning all the money they generate is more palatable. E. N. Elliott stated: “The person of the slave is not property, no matter what the fictions of the law may say; but the right to his labor is property, and may be transferred like any other property…”

Likewise modern apologists for IP explain the works themselves are not property, but the right to use them are.

Critique of Abolitionists

Like today’s Free Culture reformers, yesterday’s Abolitionists were called communists, extremists, fanatics — and in the case of the latter, heretics:

The agitation of the abolition question had commenced…under the auspices of the Red Republicans…and by anti-slavery missionaries it had been introduced into our Northern States….

(We) discussed (slavery) not only in the light of revelation and morals, but as consistent with the Federal Constitution and the Declaration of Independence; until many of those who had commenced their career of abolition agitation by reasoning from the Bible and the Constitution, were compelled to acknowledge that they both were hopelessly pro-slavery, and to cry: “give us an anti-slavery constitution, an anti-slavery Bible, and an anti-slavery God.” To such straits are men reduced by fanaticism. It is here worthy of remark, that most of the early abolition propagandists, many of whom commenced as Christian ministers, have ended in downright infidelity. [11]

The rhetorical similarities go on and on; the above represents but a sample.

The very existence of institutionalized slavery in the U.S. goads us to question how it was possible, and ask ourselves how we would have behaved in a slave society. What would we have done if we had been slaves? Would we have risked our lives to gain freedom? What if we had owned slaves? Would we have freed them? Would we have risked our own safety to help the enslaved gain freedom? Or would we have labeled antislavery activists as extremists, as excessively sentimental, irrational, and emotional? Would we have maintained the status quo, or tried to change it? How much would we have been willing to risk to do the right thing? These questions should haunt us. We can’t go back in time to find out, but we can look at ourselves today and wonder, How will the future judge us?

References:

[1] http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Jack_Valenti#Testimony_to_the_US_House_of_Representatives_.281982.29

[2] http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28148/28148-h/28148-h.htm

[3] http://www.facebook.com/posted.php?id=772612641&share_id=353581805371&comments=1

[4] http://techdirt.com/articles/20091106/0128326820.shtml

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underground_Railroad#cite_note-1

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underground_Railroad

[7] http://history.howstuffworks.com/american-civil-war/underground-railroad2.htm and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fugitive_Slave_Act_of_1793.

[8] See http://gawker.com/5216918/martin-luther-king-jrs-children-are-shameless-greedy-shakedown-artists and especially this comment.

[9] http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/documents/documents_p2.cfm?doc=22

[10] http://www.copyrightalliance.org/content.php?key=videos

[11] http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28148/28148-h/images/x.png

[12] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republican_Party_%28United_States%29#History

[13] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swedish_Pirate_Party