About a year and a half ago I released my film Sita Sings the Blues under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license. That license allows truly free distribution, including commercial use, as long as the free license remains in place. But my experience is that most people see the words “Creative Commons” and simply assume the license is Non-Commercial — because the majority of Creative Commons licenses they’ve seen elsewhere have been Non-Commercial.

This is a real problem. Some artists have re-released Sita remixes under Creative Commons Non-Commercial licenses. Many bloggers and journalists assume the non-commercial restrictions, even when the license is correctly named:

The film was made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License, allowing third parties to share the creative content for non-commercial purposes freely as long as the author of the content is attributed as the creator of the work. —Frontline, India’s National Magazine

Initially I tried to explain what “ShareAlike” means, and asked “Sita” remixers to please switch to ShareAlike, per the terms of the ShareAlike license under which I released it. I felt like an ass; I don’t want to be a licensing cop. After a while, mis-identifications of the project’s license became so widespread I gave up trying to correct them. “Creative Commons” means “Non-Commercial” to most people. Fighting it is a sisyphean task.

So I’m stuck with a branding problem. As long as I use any Creative Commons license, most people will think it prohibits commercial use. Hardly anyone seems to register, let alone understand, CC-SA. Worse, those who do notice the ShareAlike marker combine it with Non-Commercial restrictions on their re-releases, which compounds the confusion (CC-NC-SA is the worst license I can imagine).

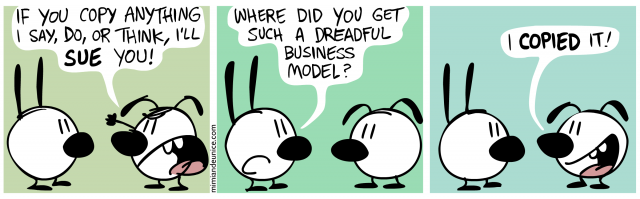

ShareAlike is an imperfect solution to copyright restrictions, as it imposes one restriction of its own: a restriction against imposing any further restrictions. It’s an attempt to use copyright against itself. As long as we live in a world wherein everything is copyrighted by default, I will use ShareAlike or some other Copyleft equivalent to attempt to maintain a “copyright-free zone” around my works. In a better world, there would be no automatic copyright and thus no need for me to use any license at all. Should that Utopia come about, I will remove all licenses from all my work. Meanwhile I attempt to limit other peoples’ freedom to limit other peoples’ freedom.

It would be nice if the Creative Commons organization did something to address this branding confusion. We suggested re-branding ShareAlike licenses as CC-PRO, but given that Creative Commons’ largest constituency is users of Non-Commercial licenses, it seems unlikely (but not impossible!) that they would distinguish their true Copyleft license with a “pro” brand.

It would also be nice if everyone, including and especially representatives of Creative Commons, referred to their licenses by their names, instead of just “Creative Commons.” “Thank you for using a Creative Commons license,” they tell me. You’re welcome; I would thank you for calling it a ShareAlike license. Almost every journalist refers to all 7 licenses as simply “Creative Commons licenses.” And so in the popular imagination, my ShareAlike license is no different from a Non-Commercial, No-Derivatives license.

This branding crisis came to a head recently when the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation banned all Creative Commons licensed music in its shows:

The issue with our use of Creative Commons music is that a lot of our content is readily available on a multitude of platforms, some of which are deemed to be ‘commercial’ in nature (e.g. streaming with pre-roll ads, or pay for download on iTunes) and currently the vast majority of the music available under a Creative Commons license prohibits commercial use.

In order to ensure that we continue to be in line with current Canadian copyright laws, and given the lack of a wide range of music that has a Creative Commons license allowing for commercial use, we made a decision to use music from our production library in our podcasts as this music has the proper usage rights attached. link

The Creative Commons organization wants to get the CBC to separate out its different licenses. They could help by calling their licenses by their different names. If the Creative Commons organization itself calls them all “Creative Commons Licenses,” how can they expect others to distinguish the licenses from each other?

Perhaps Creative Commons should only offer the Non-Commercial/No Derivatives licenses everyone associates with the name. Then they could create a new name/brand for their Free licenses. FreeCommons? CultureSource? CopyLove?

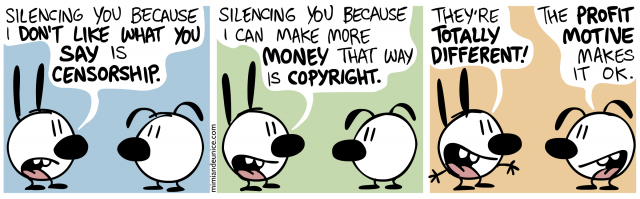

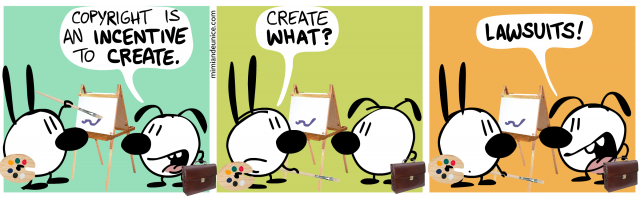

Meanwhile, I’m wondering how to clearly communicate my work is COPYLEFT. In addition to the CC-SA license, if there’s room I write “COPYLEFT, ALL WRONGS REVERSED”. Unfortunately, the term “Copyleft” is growing increasingly meaningless as well. For example, Brett Gaylor’s mostly excellent film RIP: A Remix Manifesto gets a lot of things right, but it misunderstands and misuses the term “copyleft”. Copyleft actually means this:

the right to distribute copies and modified versions of a work and requiring that the same rights be preserved in modified versions of the work. In other words, copyleft is a general method for making a program (or other work) free, and requiring all modified and extended versions of the program to be free as well. -Wikipedia

But in RIP it means this:

See that dollar sign with the slash in it? That means Non-Commercial restrictions, which are most definitely NOT Copyleft.

Anyone introduced to the word “Copyleft” in that film won’t understand what Copyleft actually means in terms of licenses.

I need a license that people understand. I’m tempted by the WTFPL but I would have to fork it to add a copyleft provision. The Do Whatever You Want And Don’t Restrict Others From Doing Whatever They Want Public License? WTFDROPL?

Are there any other useable Copyleft licenses out there that aren’t associated with non-commercial restrictions? I’m open to suggestions.

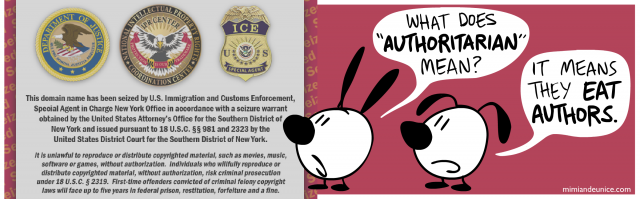

Q. Who owns culture?

Q. Who owns culture?