Bob Ostertag is a musician and experimental audio artist based in San Francisco. He has been performing and recording since the 1970s. In this article, he describes the recording industry from the point of view of an experienced musician, and explains why most musicians today would be much better off sharing music via the Internet than signing standard industry recording contracts. He also discusses the larger issue of what happens to society as more and more of our culture gets locked down under centralized corporate control. Bob practices what he preaches: his music is available for download from his web site, bobostertag.com.

(This article is now also running over at AlterNet.)

In March 2006 I posted on the Web all of my recordings to which I have rights, making them available for free download. This included numerous LPs and CDs created over 28 years [1]. I explained my motivations in a statement on the Web site:

I have decided to make all my recordings to which I have the rights freely available as digital downloads from my web site. […] This will make my music far more accessible to people around the globe, but my principal interest is not in music distribution per se, but in the free exchange of information and ideas. “Free” exchange is of course a tricky concept; more precisely, I mean the exchange of ideas that is not regulated, taxed, and ultimately controlled by some of the world’s most powerful corporations… [2]

One year later, I continue to be amazed at how few other musicians have chosen this route, though the reasons to do so are more compelling than ever. Why do musicians remain so invested in a system of legal rights which clearly does not benefit them?

When record companies first appeared, their services were required in order for people to listen to recorded music. Making and selling records was a major undertaking. Recording studios and record manufacturing plants had to be built, recording technology and techniques developed. Records not only had to be manufactured but also distributed and advertised. Record executives may have been crooked in their business practices, callous about music, or racist in their treatment of artists, but the services the companies provided were at least useful in the sense that recorded music could not be heard without them. Making recorded music available to the general public required a significant outlay of capital, which in turn required a legal structure that would provide a return on the required investment.

The contrast with the World Wide Web today could not be more striking. Instant, world-wide distribution of text, image, and sound have become automatic, an artifact of production in the digital realm. I start a blog, I type a paragraph: instant, global “distribution” is a simple artifact of the process of typing. Putting 28 years of recordings up on my Web site for free download was a simple procedure involving a few hours of effort yet resulting in the same instant, free, world-wide distribution. It makes no difference if 10 people download a song or 10,000, or if they live on my block or in Kuala Lumpur: it all happens at no cost to either them or me other than access to a computer and an Internet connection.

So much for distribution. What about production? Almost none of my releases were recorded in a recording studio provided by a record company. They were either recorded on-stage, in schools or radio stations, or in living rooms, bedrooms, and garages with whatever technology I could cobble together. They are made either by myself alone or with a small handful of close collaborators. In one sense this is atypical, because I intentionally developed an approach to recording that was premised on never needing substantial resources, with the explicit goal of maintaining maximum artistic autonomy. Yet while this approach may have been unusual 20 years ago, it is less and less so today as digital technology has drastically reduced the cost of recording. There are very few recording projects today that actually require the resources of the sort of high-end recording studios record companies put their artists in (and for which the artists then pay exorbitantly – bills which must be paid off before the musicians see any royalties from their recordings). Just as the Web has changed the character of music distribution, laptops loaded with the hardware and software necessary for high-quality sound recording and editing have changed the character of music production.

Record companies are not necessary for any of this, yet the legal structure that developed during the time when their services were useful remains. Record companies used to charge a fee for making it possible for people to listen to recorded music. Now their main function is to prohibit people from listening to music unless they pay off these corporations.

Or to put it slightly differently, they used to provide you with the tools you needed to hear recorded music. Now they charge you for permission to use tools you already have, that they did not provide, that in fact you paid someone else for. Really what they are doing is imposing a “listening tax.”

Like all taxes, if you don’t pay you are breaking the law, you are a criminal! Armed agents of the state have shown up at private residences and taken teenagers away in handcuffs for failure to pay this corporate tax. It is worth noting how draconian state coercion has been in this field in comparison to many others. For example, almost everyone I know (including myself) has a unpaid copy of Microsoft Word on their computer. I am certain that some kids who have run into legal trouble for sharing music without paying the corporate tax also had unpaid copies of Microsoft Word on the very same hard disks that were taken as “evidence” of their musical crimes. Yet no state agents are knocking on the doors of our houses to see if we have pirated software. Music alone is singled out for this special treatment.

You would think that musicians would be leading the rebellion against this insanity, but most musicians remain firmly committed to the idea of charging fees for the right to listen to their recorded music. For rock stars at the top of the food chain, this makes sense economically (if not politically). The entire structure of the record industry is built around their interests, which for all their protesting to the contrary dovetails fairly well with those of the giant record companies [3].

But the very same factors that make the structure of the record business favor the interests of the sharks at the top of the food chain work against the interests of the minnows at the bottom, who constitute the vast majority of people actually making and recording music. Most records, in fact, produce good money for corporations and little or none for the musicians. This is because the recording studios and engineers, art departments, advertising departments, A&R departments, legal departments, limo services, tour agencies, caterers, and distribution networks that swallow up the sales revenue for all but the big hits are owned by these very same corporations. Records that sell tens of thousands don’t “break even” not because no money comes in, but because all the money goes to keeping the corporation in the black. Revenue for the corporation starts coming in with the first CD sold, royalties for artists don’t kick in until every part of the bloated corporate beast is adequately fed.

What exactly are these corporations? To begin with, we should note that the major “record companies” are not actually record companies at all but huge media conglomerates. Most “independent” labels are owned by a corporate label. Each “major” is in turn owned by an even bigger corporation, and so on up the food chain. At the top of the chain sit a tiny handful of media giants: Time Warner, Disney, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, Viacom (formerly CBS) and General Electric. These corporations are among the world’s largest. All are listed in Fortune Magazine’s “Global 500” largest corporations in the world. They have integrated both horizontally (owning lots of record labels, lots of newspapers, and radio stations) and vertically (controlling newspapers, magazines, book publishing houses, and movie and TV production studios, as well as print distribution systems, cable and broadcast TV networks, radio stations, telephone lines, satellite systems, web portals, billboards, and more).

This incredible concentration of power over news, entertainment, advertising, music, and media of all kinds is a recent phenomena, and is fueled by the very same digital technology that has made the Web and the recording-studio-in-the-bedroom possible. In 1983, 50 corporations dominated US mass media, and the biggest media merger in history was a $340 million deal. By 1997 the 50 had shrunk to 10, one of which was created in the $19 billion merger of Disney and ABC. Just three years later, the end of the century saw the 10 shrink to just five amidst the $350 billion merger of AOL and Time Warner, a deal more than 1,000 times larger than “the biggest deal in history” just 17 years before. As Ben Bagdikian, author of the classic study The New Media Monopoly noted, “In 1983, the men and women who headed the first mass media corporations that dominated American audiences could have fit comfortably in a modest hotel ballroom… By 2003, [they] could fit in a generous phone booth.” [4]

These companies own the most powerful ideology-manufacturing apparatus in the history of the world. It is no wonder they have convinced most musicians, and most everyone else, that the entire endeavor of human music-making would come to a screeching halt if people were allowed to listen to recorded music without first paying a fee – to these corporations. I know many musicians for whom making records in an environment dominated by corporate giants has been an exhausting and thankless task from which they have derived little or no gain, yet they remain convinced that taking advantage of the free global distribution offered by the Internet would constitute some sort of professional suicide.

Here is how the structure of this industry ruins the aspirations of independent-minded musicians and labels. Mainstream CDs sell in really large numbers only for a short window of time, usually while songs from the CD are on the radio. Unless those CDs are on the shelves of stores while the songs are on the air, potential sales are lost. In order to get stores to order large numbers of CDs in advance, the industry evolved with the norm that stores can return unsold CDs at any time. If your company sells pants, or toasters, or bicycles, retailers cannot do this, but record shops can. As a result, record labels must have more money in the bank per unit sales – be more capitalized – than other kinds of companies. Unfortunately, with almost all independent labels this is far from the case. Most are started by music fans driven in to the business by their passion for the music they love. They operate on a shoestring. They send out a bunch of records and hope for the best. Sales might look good at first, but at some later point they get swamped with returns and they have a cash flow crisis. To survive the crisis they engage in creative bookkeeping, telling themselves it is OK because they are really doing this in the interest of the artists, and when things improve everything will get sorted out. But things only get worse, until they collapse or they get bought by a bigger company with more capital. If they collapse, artists don’t get paid and there is a storm of mutual recrimination. If they get bought, the company that buys them is generally only interested in the top selling artists in the catalog, and may well take all the other titles out of print. I know one artist who had ten years of his recordings vanish into the vault of a big label that bought the little label he recorded for. He approached his new corporate master and asked to buy back the rights of his own work and was refused. In the company’s view, his work did not have sufficient market potential to justify releasing it and putting corporate market muscle behind promoting it, but neither did they want his work released by anyone else to compete with the products they did release. From their perspective it was a better bet to just lock it up.

I could relate many more anecdotes here, or delve deeper into the structure of the industry, but I think what has been said so far should suffice. Among people in my immediate social circle of musicians, John Zorn, Mike Patton, and Fred Frith have, over the years, sold CDs in sufficient quantity to actually make money. For all the rest of us, selling recordings in whatever format has been a break-even proposition at best. Not only have we not made any money, for most people in the world our music is unavailable. My works provide an excellent example.

-

My first LP, with the Fall Mountain ensemble, was released on Parachute, a small label run by Eugene Chadbourne which folded long ago and the music has been unavailable ever since.

-

My Getting A Head and Voice of America were released on Rift, a small label run by Fred Frith which suffered the same fate. It remained unavailable until I put it on line for free.

-

My Attention Span, Sooner or Later, Burns Like Fire, and Say No More were released on RecRec in Switzerland, a label launched by a music fan that went through exactly the trajectory typical of small labels I described above. By the time that I, and other artists recording for the label, discovered that we were being cheated out of our royalties the label was already collapsing. Here again, all this music remained unavailable until I put it on line for free. Since then, several thousand people have heard it.

I could continue this list but there are a lot of CDs and the stories would become dully repetitive. Of course, my music is pretty far off the beaten path. But if I had instead spent the last decades playing in rock bands that had released a series of recordings that each sold in the tens of thousands, the details would be different but the result would be the same. This is the structure of music distribution it is allegedly in the interests of musicians to defend.

There is now a very simple alternative, which is to simply post your music on the web. No, you won’t make any money from it, but the odds are overwhelming that you would never make any money from it anyway if you charged for it. And by posting it on the Web a remarkable thing happens. People all over the world can actually hear it. When I was making my music available for sale on CD, I would often hear from people who had spent years unsuccessfully trying to find a copy of a particular CD, and these were dedicated hard core listeners, who put a lot of their free time into music. Now anyone with even a passing interest can find my music easily and hear it.

People have actually been convinced that if it were not possible to charge fees for listening to recorded music, there would be no “incentive” to play music. It’s time to take a step back and see the big picture. As recently as 60 years ago, most people who made their livelihood from music viewed the recording industry as a threat to their livelihood, not the basis of it. Given the mountains of money that big stars have made during the intervening decades, this fear has generally been viewed in retrospect as hopelessly naïve. But consider the following: A few years ago I performed in the cultural festival organized by the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, and witnessed the parade and dance party which is this festival’s culminating event. The parade brought roughly half a million people into the streets, including participants and observers. It took hours for the parade to slowly move through its course. Every contingent in the parade had its own choreography and music. The participants danced through the street, and many spectators danced alongside. So that’s half a million people dancing in the street for several hours. The parade ended in a 12-hour dance party attended by over 20,000, featuring seven different pavilions with non-stop music in each. Before the era of recording, the number of musicians required to keep half a million people dancing in the street for six hours, and then 20,000 dancing for 12 hours more, would have easily run in to the thousands. At the event I attended, the musicians involved numbered exactly one. No contingent in the parade included a live musician – all were dancing to recordings. All the music at the dance party was recorded as well. In the largest pavilion, at the climax of the party, an actual live singer, Chaka Kahn, emerged in a blaze of fireworks and lights to sing a short medley of her hits – to recorded accompaniment.

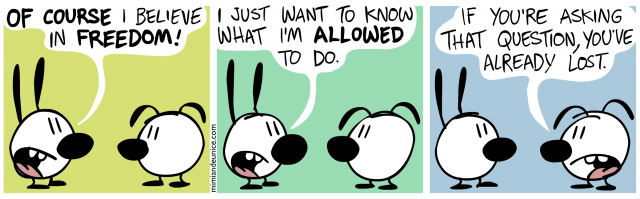

Humans have walked this earth for about 195,000 years. We don’t know exactly when music emerged, but it was certainly a very long time ago, long before recorded history. There is evidence that music may have been integral to the evolution of the human brain, that music and language developed in tandem. The first recording device was invented just 129 years ago. The first mass-produced record appeared just 110 years ago. The idea that selling permission to listen to recorded music is the foundation of the possibility of earning one’s livelihood from music is at most 50 years old, and it is a myth. The fact that most musicians today believe in this myth is an ideological triumph for corporate power of breathtaking proportions.

I should note that I do have serious reservations about the emerging culture of on-line music, but they have nothing to do with money. My music is made for sustained, concentrated listening. This kind of listening is increasingly rare in our busy, caffeine-driven, media-drenched, networked world. I suspect it is even rarer for music that was downloaded for free, broken up and shuffled through fleeting “playlists”, and not objectified in an object that one can hold in one’s hand, file on the shelf, or give to a friend. But this concern has nothing to do whether we charge money to hear recorded music, and everything to do with how we live in a culture in which there is a surplus of information and a scarcity of time to pay attention.

The issues involved here are hardly limited to music, but extend outward to a legal and corporate structure that shapes our culture so profoundly its importance can hardly be exaggerated. Music is no longer just music but a small subset of a corporation’s properties. Property rights have become so absurdly swollen that they now constitute a smokescreen hiding a corporate power grab on a scale rivaling that of the great robber barons of the nineteenth century. Instead of grabbing land or oil, today’s corporate barons are seizing control of culture. They are using the legal construct of property to extend the reach of corporate power into parts of our lives that were previously beyond their grasp.

There are so many shocking anecdotes one could relate in this regard; here is one from my own recent experience. If it seems trivial at first glance, it is because it is. That is precisely my point, as you will see if you bear with me.

It has been my privilege to have John Cooney as a student. John is young, bright, enthusiastic, hard-working, politically engaged, and artistically gifted. During his freshman year at UC Davis, he made a short animation about global warming that won the Flash Contest prize from Citizens for Global Solutions, and the Environmental Award of the Media That Matters Film Festival. He also made a computer game that he put on-line for free, and that was listed as a “Top Free Online Games” by Freeonlinegames.com, a “Game of the Week” by ActionFlash.com, and a “Featured Game,” by Addicting Games. John’s game also made the “Flash Player Top Games List,” and was even the subject of a story on BBC World News.

Not bad for an 18-year old college freshman. But both his projects resulted in cease-and-desist letters from corporate lawyers, including one from Tolkien Enterprises demanding that he not refer to an animated character in a game he was offering on-line for no charge as a “hobbit.” None of this involved high stakes or dire consequences. John’s game no longer features a “hobbit.” This case is trivial compared to parents getting sued for vast sums because their kids are downloading pop songs, or the unhappy plight of Eyes on the Prize, a film which beautifully documents the civil rights movement in the US, yet was withdrawn from circulation because its makers could not afford to renew all the necessary permissions on the incidental music that “leaked” into the film via documentary footage (which included a substantial payment to the copyright holders of the “happy birthday” song as the film shows Martin Luther King Jr.’s family at home celebrating the civil rights leader’s birthday).

But John’s experience is important precisely because it did not involve important people or high-profile issues. Even though there was no realistic possibility that anyone would think Tolkien Enterprises had somehow endorsed or been involved in John’s project, the mere fact that someone, somewhere was making new, independent culture using Tolkien Enterprises’ copyrighted character was enough to set the corporate reflexes in motion. The key thing here is the convergence of corporate power with the growth of the World Wide Web. If John had just shown his game in class and not put it on the Web, Tolkien Enterprises would have never known or cared. If his animation had not won an award, there would likely have been no legal threats. Together, the episodes offer an elegant demonstration of how copyright law punishes success and deters creative use of the World Wide Web.

Anything on the Web is available to anyone, which is of course both its promise and its peril. Corporate legal departments can write automated programs that crawl through the Web 24/7 searching for copyrighted works. The “hits” then generate threatening letters that intimidate anyone who doesn’t have deep pockets and a lot of time on their hands. The cost to the sender is almost nil; the cost to society is, in a literal sense, immeasurable.

Getting a threatening letter for a corporate legal department is not a pleasant experience for anyone, least of all an 18-year old kid. Keep in mind that more and more students turn in homework assignments via the Web, and not just in college but in high school too. All of that work is now exposed to the corporate vultures.

“Property rights” have bloated to the point where they can dictate the content of freshman art projects. But that is not all. Altogether more and more of what we do in our lives passes through the Web. People invite friends to parties, view art, listen to music, play games, have political discussions, date and fall in love, post their family photo albums, share their dreams, and play out sexual fantasies – all on line. Since corporate legal departments claim their copyright privileges extend to anything on the Web, the result is a huge extension of corporate power into private lives and social networks.

But that is just the beginning of the story, for the accelerating rate of technological change continues to push digital technology further and further into our lives in just about any direction you might look. To pick just one example, boundaries between our bodies and minds and our technology are blurring. Cochlear implants, for example, now allow deaf people to hear via computer chips loaded with copyrighted software which are implanted in their skulls and in response to which their brains reconfigure, growing new synapses while unused synapses fade. Cochlear implants are wirelessly networked to hardware worn outside the body which usually connects to a mic, thus allowing the deaf to hear the sound environment around them. But the external hardware can just as easily be plugged into a laptop’s audio output for a direct audio tap into the Web.

When the Web extends into chips in our skulls, where is the boundary between language that is carved up into words that are corporately owned and language that is free for the thinking?

I don’t wish to be sensationalist. We are not all about to turn into corporately-owned cyborgs. But I do wish to point out that the issues around turning culture into property are urgent, and far-reaching. Society is not well-served if we treat specific matters like downloading music on the Web as isolated problems instead of one manifestation of a vastly bigger struggle in which much more is at stake.

1 The original recording titles includes Early Fall, Getting A Head, Voice of America, Sooner or Later, Burns Like Fire, Fear No Love, Pantychrist, Like A Melody, No Bitterness, DJ of the Month, Say No More, Say No More in Person, Verbatim, and Verbatim Flesh and Blood.

3 Prince is the one notable exception here – a megastar who has used the Internet to build a music distribution infrastructure controlled by him and not a Fortune 500 company.

4 Ben H. Bagdikian, The New Media Monopoly, Boston: Beacon, 2004.

Back in late 2006, Matthew Gertner (of AllPeers) and I did a mutual interview about copyright reform. It was a fascinating and wide-ranging conversation, and he’s

Back in late 2006, Matthew Gertner (of AllPeers) and I did a mutual interview about copyright reform. It was a fascinating and wide-ranging conversation, and he’s