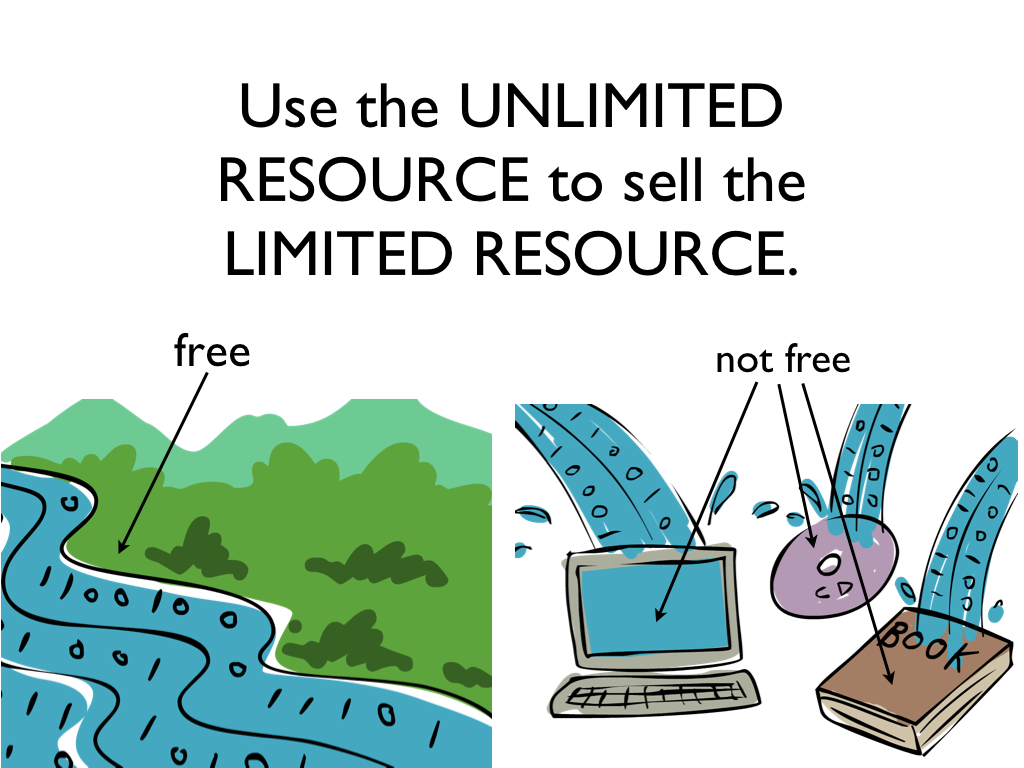

Content is an unlimited resource. People can now make perfect copies of digital content for free. That’s why they expect content to be free — because it is in fact free. That is GOOD.

Think of “content” — culture — as water. Where water flows, life flourishes.

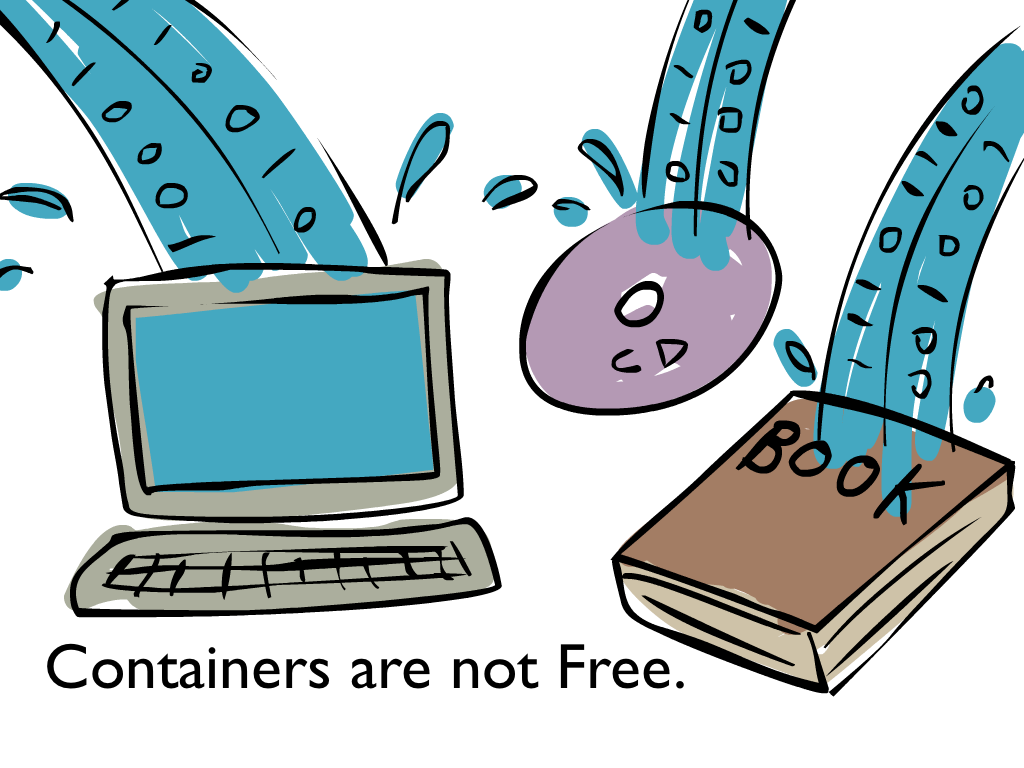

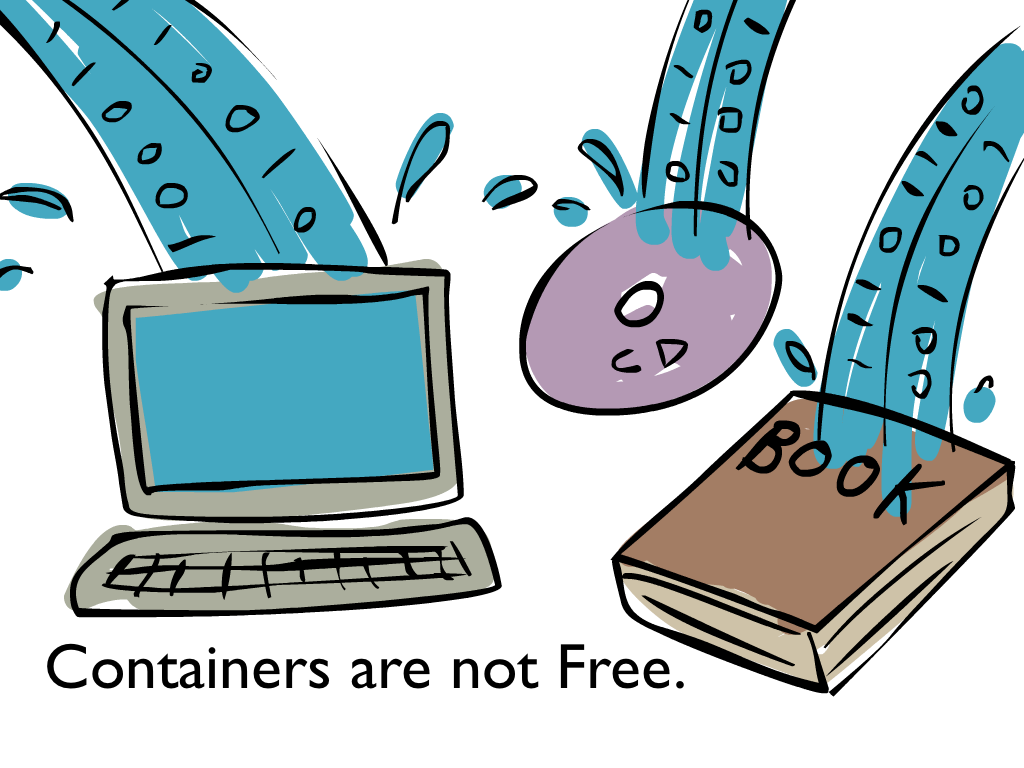

Containers — objects like books, DVDs, hard drives, apparel, action figures, and prints — are not free. They are a limited resource. No one expects these objects to be free, and people voluntarily pay good money for them.

Think of “containers” — books, discs, hard drives — as jugs and vessels. These containers add utility to and increase the value of the water. If you can get water for free in the public river, great — that doesn’t reduce the value of vessels. Quite the contrary: when rivers flow, the utility and value of water vessels increases.

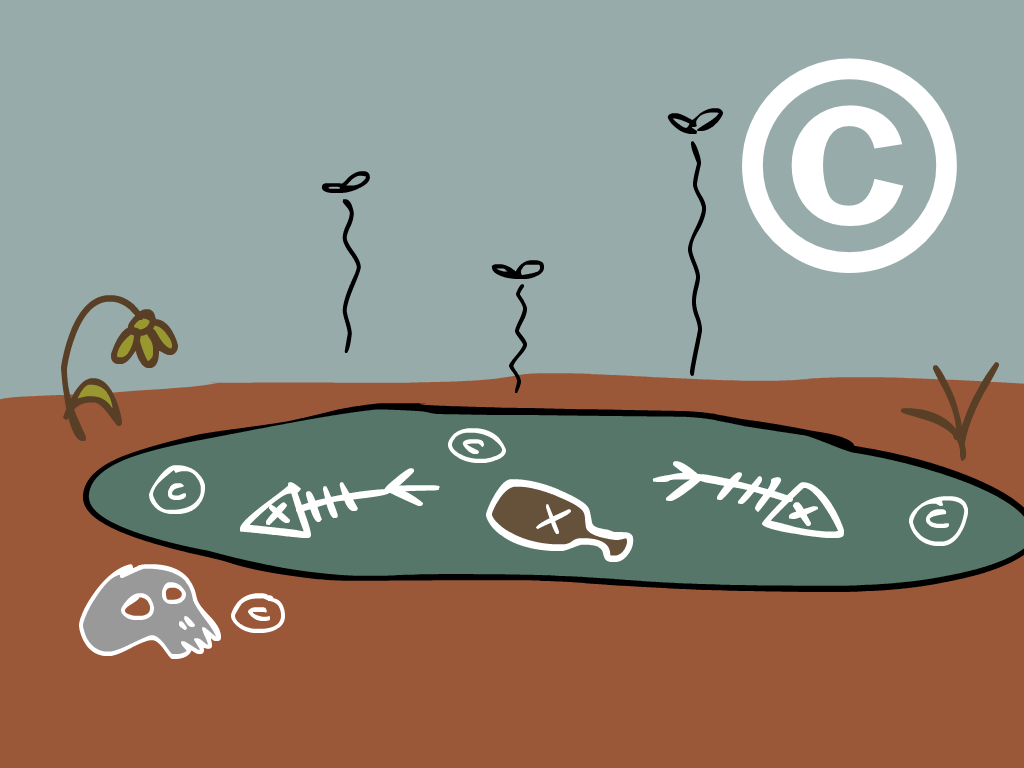

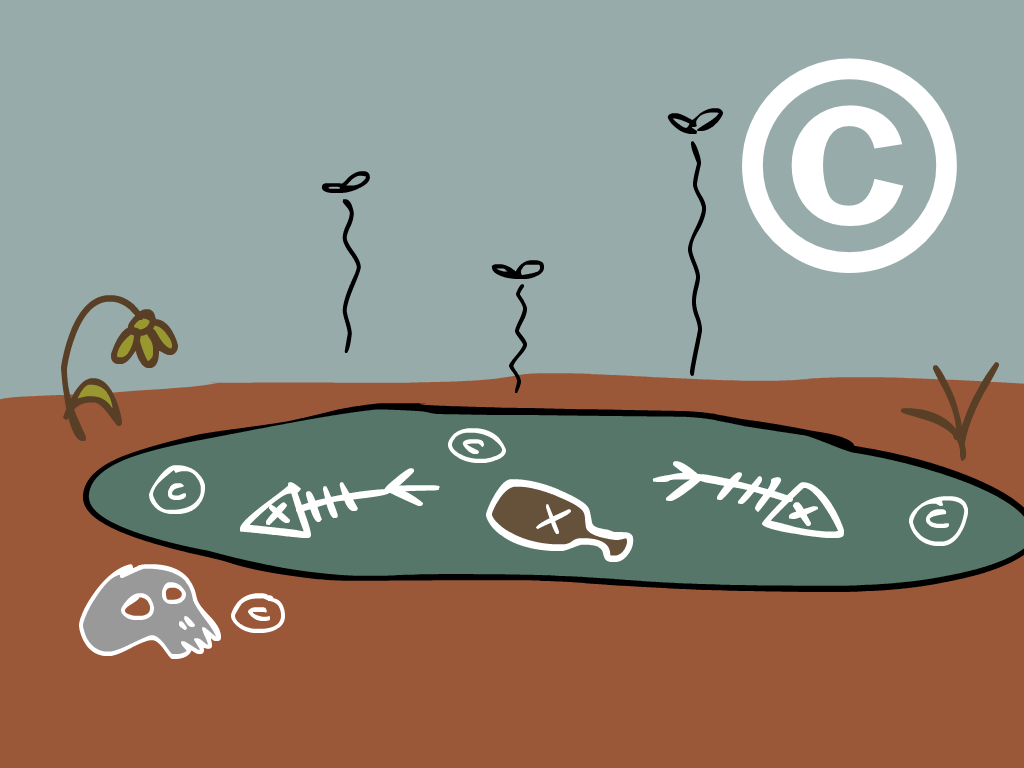

Continuing this metaphor: copyright monopolies are an attempt to dam up and control all the rivers, reducing them to a trickle. When Big Media succeeds locking up culture, it’s like in closing off water: they get a stagnant pool that turns to poison. Fish die and mosquitoes swarm, because the water has no source to flow from nor destination to flow to.

(That’s how we get things like this.)

(That’s how we get things like this.)

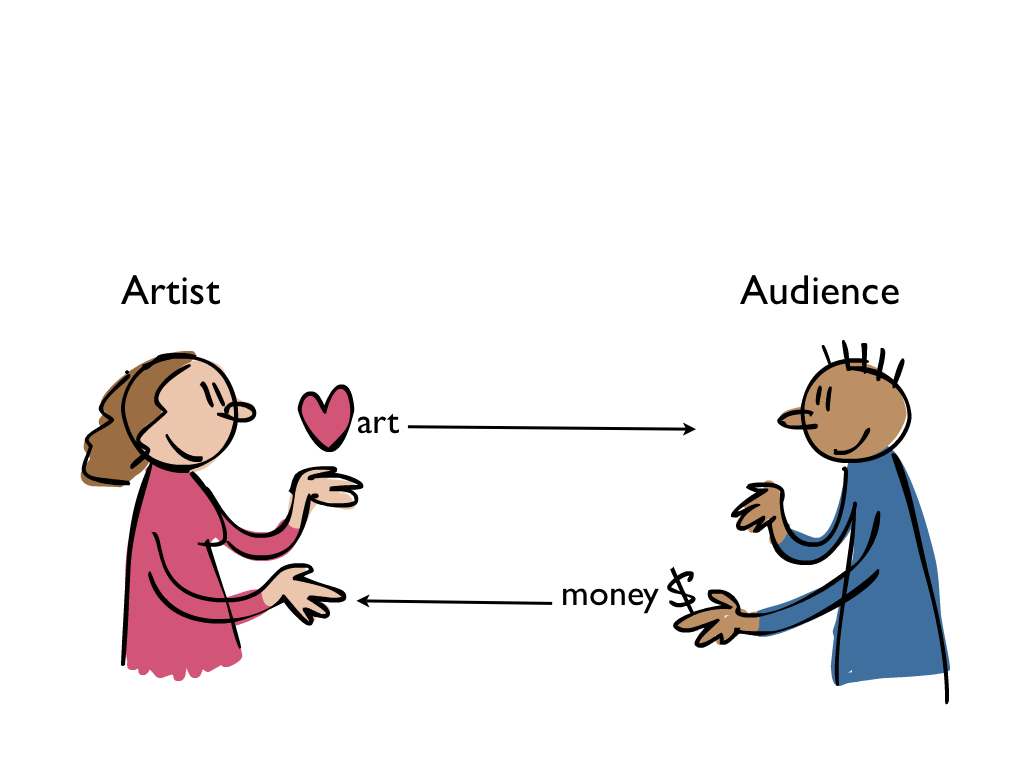

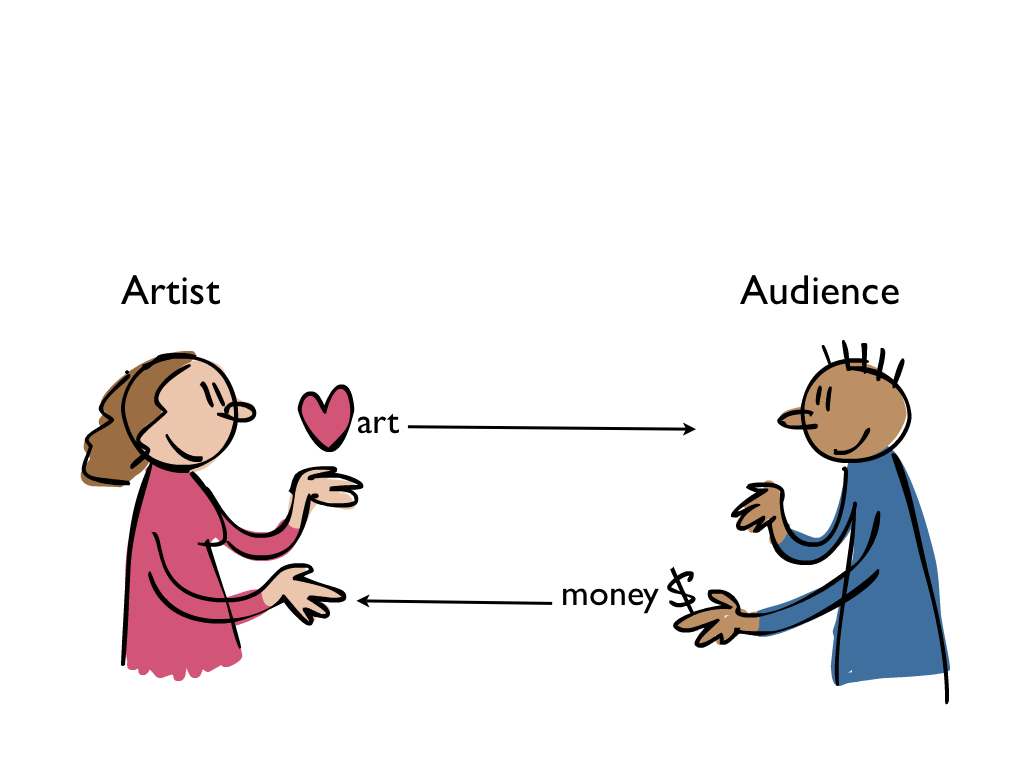

Artists don’t “own” culture, but we do own our names (attribution). Any artist who has enjoyed a community of fans knows how the power in their name is generously granted by audiences. Our audiences want us to thrive. They want their money and support to reach us.

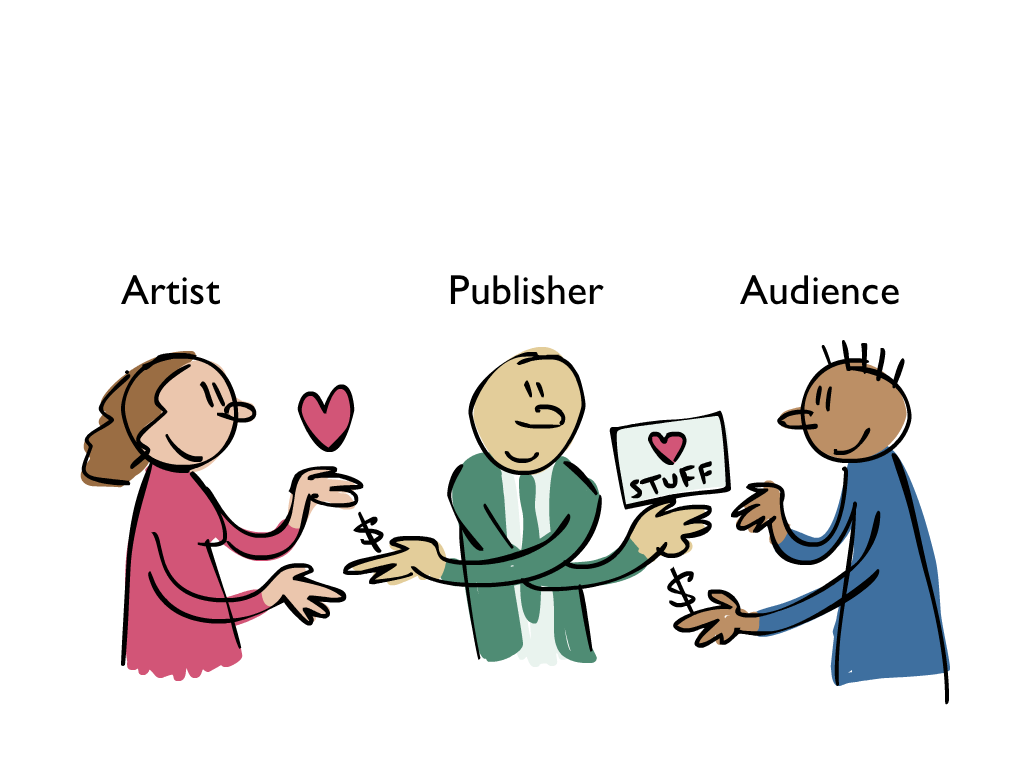

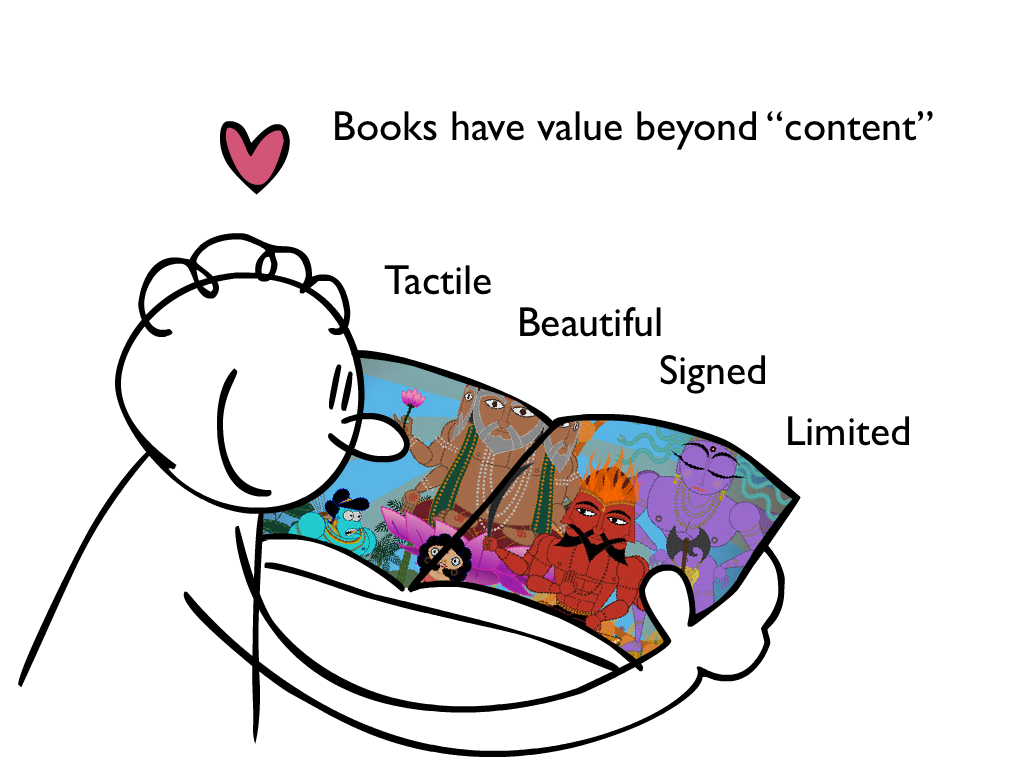

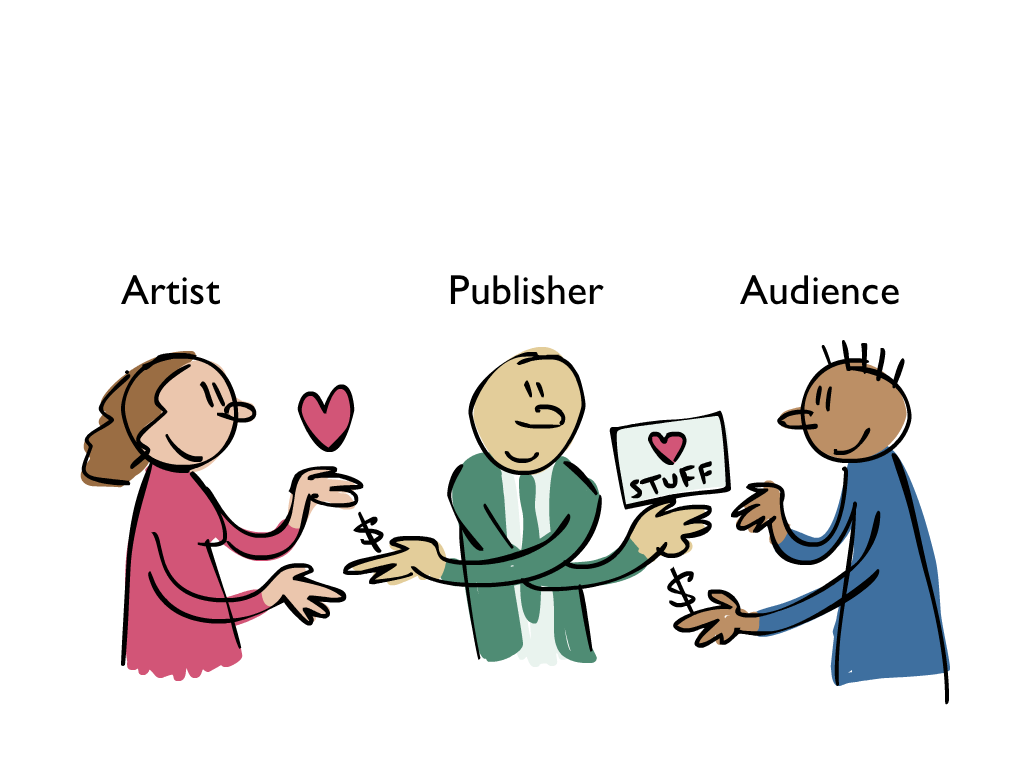

Therefore an artist’s cooperation with a merchandiser is valuable. A signed book is worth more than an unsigned one. Merchandisers who cooperate with artists — share revenue with them — get the blessing of both artist and audience and can sell more objects for more money.

Under the Creative Commons Share Alike license, Sita Sings the Blues-containing objects can be manufactured and sold by anyone without my permission. But whoever shares revenue with me gets my “creator endorsed mark” or signature, and gets my fans sent to the product (via community word-of-mouth and my web site).

Competing products can nonetheless be sold without my endorsement. If they’re cheaper, of better quality, or more accessible, they might sell better than my endorsed products. Why shouldn’t they? Competition can be good. All the more incentive for any business I partner with to make their products high quality, reasonably priced and easily available. There’s no incentive to compete with a good product; if there’s a good affordable Sita Sings the Blues coffee table book or graphic novel, why should anyone bother publishing another? If they do, the competing book must have some important quality lacking in the first. If that competitor’s quality differential is so high it’s worth more than my endorsement, then good for them for doing something right.

Remember:

Free Enterprise is Free Culture too.

Common Questions about Free Content:

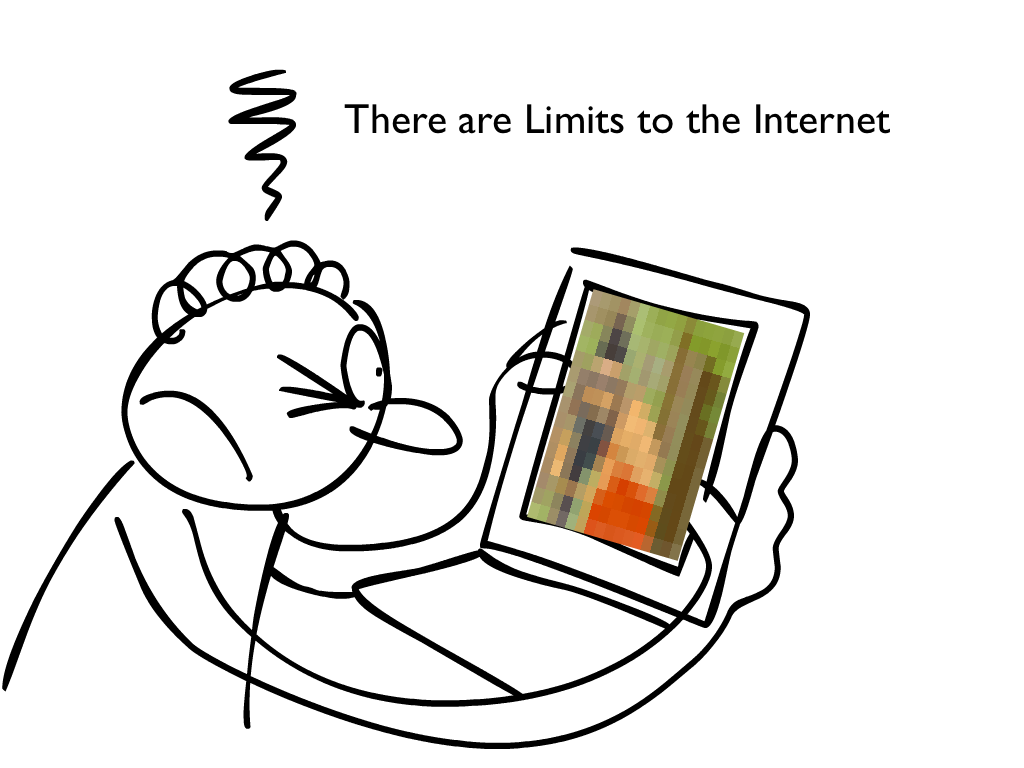

Q. Why make a book when you can get the content free on the Internet?

A. Because there are limits to the Internet. You can’t touch it or smell it. Images are restricted to screen quality and may cause eyestrain.

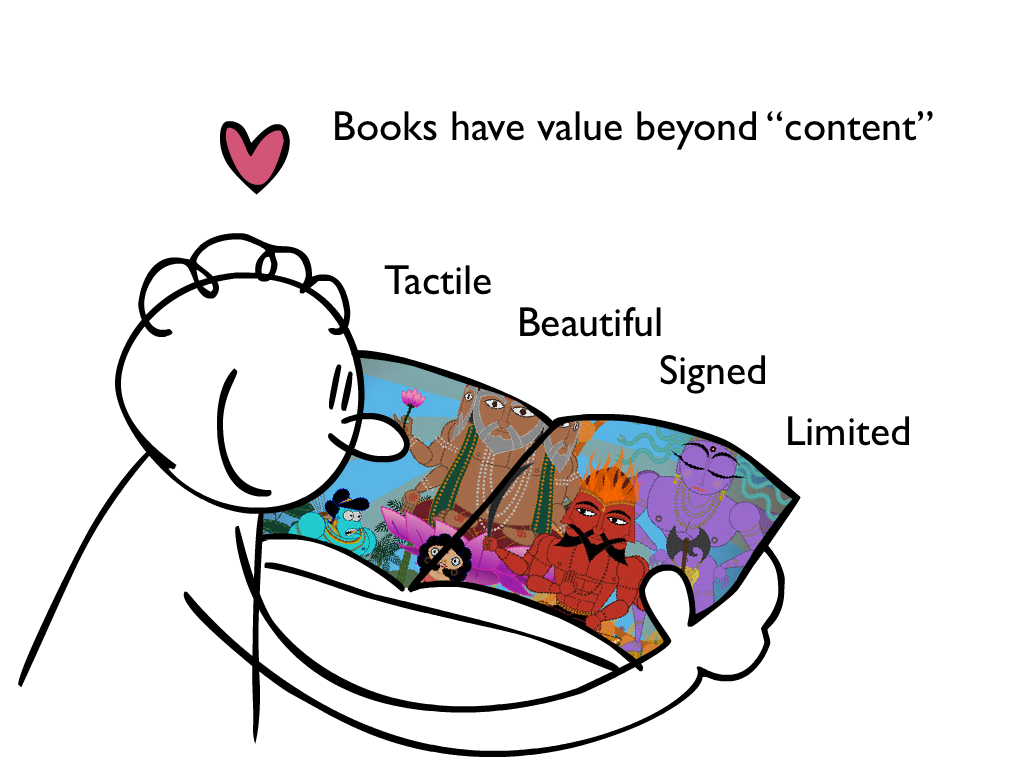

Books have value as objects beyond the intellectual wealth they embody. They are portable, tactile, and invulnerable to power outages. Art books can have even more valuable attributes: glossy coatings, embossing, reflective and matte inks, paper textures, super-high resolutions. Books can be beautiful objects in their own right. Signed books are works of art. Books can have value as collector’s items, because they are LIMITED.

Audiences seek a connection with creators. Even if the content is free, many fans desire a physical token of the work. They also want to support the artist. Merchandise — objects, like books, DVDs, apparel — acts as a medium to conduct these artist-audience transactions.

Q. Why make it free on the internet if it’s available as a book (or DVD, CD, etc.)?

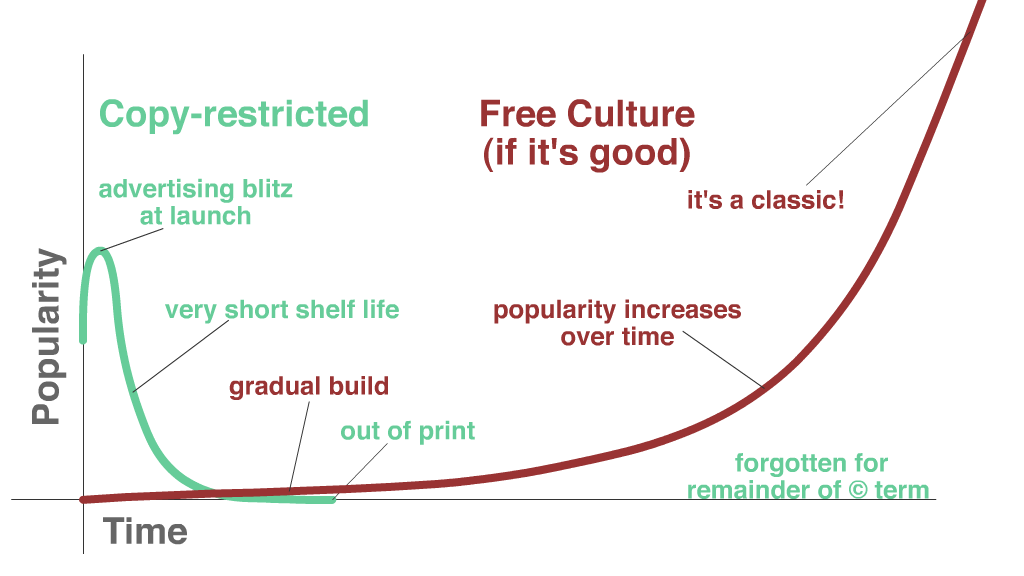

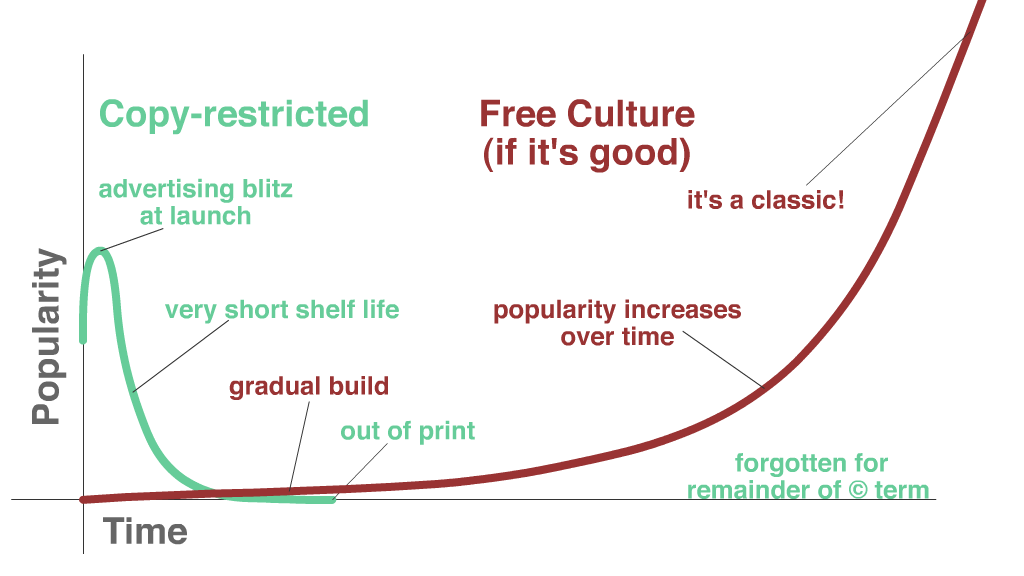

A. Because if it’s free, it can spread. If it’s good, the audience will quote it, cite it, share it, review it, and promote it. Free accomplishes everything advertising does, except it’s good not evil, free not controlled, voluntarily shared not forced down throats. Instead of spending vast sums on crappy advertising to sell “content” you’ve locked up, just free the content and let it advertise itself. Use the unlimited resource to sell the limited resource.

Q. But even with the internet, I still have to advertise!

A. Maybe. Depends on what your content and how much time you have. If what you have is good, just give it time. “Viral” growth is exponential, but it can take a while. Or you can use advertising to artificially direct audience attention to something they wouldn’t care about otherwise. If the work is not good, interest will drop off when advertising does.

That’s our vision of Free. It’s not communism. It’s not capitalism as we know it. It’s definitely not monopolies. It is Free Culture, and Free Enterprise.

(That’s how we get things like

(That’s how we get things like