Art Brodsky of Public Knowledge interviewed Nina Paley about copyright restrictions and her experiences trying to get her film Sita Sings the Blues past the copyright gatekeepers. The original interview is at “We Are Creators Too. Part 1 of 4. Today, Nina Paley’s Story”, part of the PK TV Series. We had it transcribed:

Art Brodsky: So this is Art Brodsky from Public Knowledge. We’re here with Nina Paley, who created a fabulous film called Sita Sings the Blues, which Roger Ebert raved about, and you can watch online but, unfortunately, not in a movie theater.

Nina Paley: No, no, you can watch it in a movie theater.

Art Brodsky: Oh, we can? Where?

Nina Paley: Yes.

Art Brodsky: Oh, good! Catch us up with what’s going on.

Nina Paley: Okay, so it’s having a very limited theatrical release. It’s legal. It’s totally legal, and there’s some confusion as to why I released it under the Creative Commons Share Alike license. If I had not paid off the licensors — that’s a polite way to refer to them, the “licensors” — it would not have been legal for me to offer the film for free download. I could have gone to jail for five years even for giving away for free.

It still would have been copyright infringement. So I’m not giving it away for free in order to not pay the licensing fees. I had to pay the fees in order to do that. Having done that, it’s completely legal, and because it’s completely legal, it’s like, well, I’ve got 35-millimeter prints, I’ll show them in cinemas! So it’s having an art house release, a very slow, gradual and unadvertised art house release.

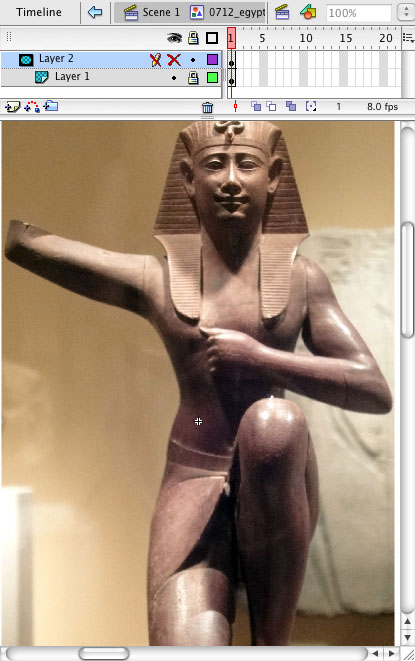

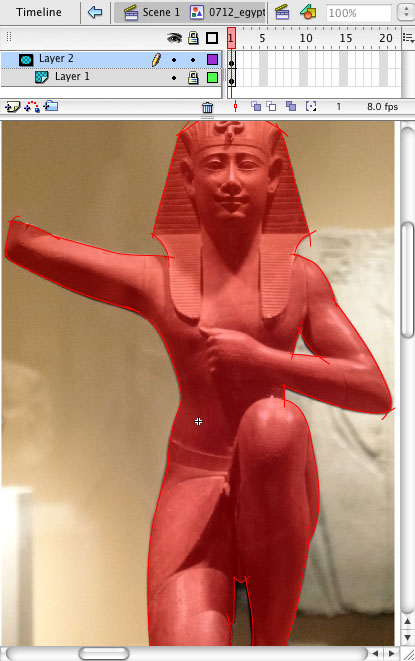

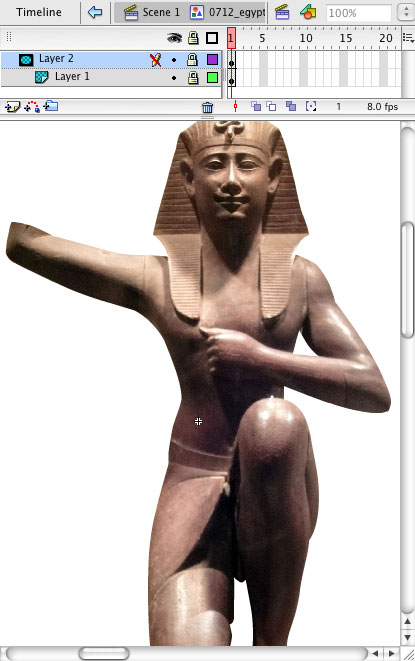

Art Brodsky: So let’s back up a little bit. You became known as much for the quality of the film, which is fabulous, with your own animation and the Indonesian shadow puppets or shadow figures and the Indian stuff, as for the copyright issues that you encountered, and this is because you used some music from 1927. Is that right?

Nina Paley: Yes, 1927, 1928. Annette Hanshaw, the recordings of which are in the public domain everywhere in the world except possibly New York State, so at some point I may have to ban the film in New York State. We’ll see how that goes, but I figure most of the world is outside of New York State. And, of course, the real problem was the songs, the lyrics that underlie the recordings.

Art Brodsky: Right. The recordings are [out of copyright], but you ran into this thing called sync rights.

Nina Paley: Yes, sync licenses. I had thought naïvely — granted, naïve — that because covers — there was no — I guess I had been thinking like these songs are available as audio. Like lots of people have recorded them, so I was thinking, “Well, the compositions and lyrics, that can’t be that difficult to use.” What I didn’t know was that it’s legal to release them on albums, it’s legal to release the sound, but once you put a picture to that, that’s not legal anymore and that’s not regulated by the government, and the licensors are free to charge anything they want. And they did their best, you know. They came up with a number, $220,000.00 approximately. That was their estimate. That’s their like little, tiny, independent feature filmmaker amount, and I couldn’t afford it.

Art Brodsky: So what eventually happened with that?

Nina Paley: I should mention all this went through intermediaries because they wouldn’t actually talk to me directly. They would — they only have time to — they’re very busy because the system is — it’s a crazy system, right? (Laughter) Like you need — everybody has to ask you permission. There’s only so much time to grant permission, so they don’t have time to talk to everybody who comes to them. They only make time to talk to paid professionals that they have relationships with, so I had to pay a lawyer at first to talk to them, and I ran out of money on that, and…

Art Brodsky: Who is the “them?”

Nina Paley: Warner/Chappell, Sony… There’s a whole list at Sita’s —

Art Brodsky: Yeah, on your Web site you list all the licenses that you had to get, which is quite amazing.

Nina Paley: Yeah. Actually, why don’t I just go there since we’re all here? Hang on a second. Okay, so the great question of who owns culture. Warner/Chappell, the biggest one. I can even tell you — I might allow — no, I think. That’s the thing. Like I’m not supposed to — I got these contracts and one of the terms of the contracts is you’re not allowed to reveal the terms of the contracts.

Art Brodsky: Ah, or else they’d have to kill you.

Nina Paley: Well, the thing is you’re supposed to — you must reveal the terms of the contracts to the distributor, but you’re not supposed to reveal them to anybody else, but the thing is the public is my distributor. So I have to reveal the terms of the contract to the people who are distributing my film, which is everyone, especially because if they want to sell DVDs, they have to pay these extra licenses. I want to make sure that they get paid, right? I mean I have to comply with the law. That’s the law. I signed a thing that said they’re gonna get paid, so I have to let people know how much to pay these corporations if they want to sell Sita DVDs. But, anyway, I can tell you the licensors are mostly Warner/Chappell, EMI Music Publishing, Sony ATV Music Publishing, Songwriter’s Guild of America, Williamson Music, Cromwell Music, Memory Lane Music and Bug Music. Most of it is held by Warner/Chappell, Sony, Williamson. Yeah, those are the ones.

Art Brodsky: And those are for the songs from 1927 which should be in the public domain.

Nina Paley: Yeah. They were supposed to be in the public domain at the very, very latest by the ’80s, but they didn’t quite make it. If they had been from 1922, it would have been okay, but they just — Congress just keeps extending copyright terms, and this is what happens and mostly, you know, one of the obvious results of this is that Annette Hanshaw’s music has become extremely obscure and many people had never heard her songs until they saw this film, which is remarkable, and the only explanation for it is copyright.

[musical interlude]

Nina Paley: And I should even mention that the CDs that have been released of her music all come from outside the United States, because no American audio distributor would want to deal with releasing something that couldn’t be sold in New York State. Maybe. They just don’t want to deal with it. So every other country in the world has more access to American cultural heritage than Americans and especially New Yorkers.

Art Brodsky: Yeah. Well, you were warned off of doing music in your film originally, right?

Nina Paley: Yeah. I mean it’s — the people in film, they just don’t want to deal with this. It’s like it’s such a mess, and you can put all this work into a film and then have it be illegal and most people respond to this climate by just — it’s like just don’t go there. Like don’t touch this. Just don’t. There’s this big gap in music starting in 1923. (Laughter) It’s just not gonna show up in films, certainly not by independent artists. Giant companies can use it. In fact, I was really struck when I was watching Wall-E, the Pixar Disney film, they had these clips from “Hello, Dolly.” And, of course, they can do that ’cause they have, you know, millions and millions of dollars and that’s what it costs. But independents like me, there’s no way we’re gonna be able to do stuff like that.

Art Brodsky: Yeah, that was one of the things that struck me. I was reading one of the interviews that you did and the first comment was, “She should have checked her rights.”

Nina Paley: Yeah.

Art Brodsky: Is there a limit to like one per — and you said you’d had a whole team of law students and professors doing this for months, right?

Nina Paley: Yeah, for years actually. I was doing — you know, I was doing my best. It’s like you’re not supposed to make a film unless you have millions of dollars to start with, like an enormous part of your budget is supposed to be just legal, which is a real disincentive for independent artists to make film. And we’re in this freaky time where suddenly the technology has become cheap enough and powerful enough so that independents, just ordinary people like me, can make films, but we’re not supposed to. Like there’s this whole legal thing that is supposed to keep us out, and so the technology is beginning to let us in, but the legal system is not.

Art Brodsky: So what has to happen for the legal system to catch up to the technology?

Nina Paley: There are so many things. I mean I think one very simple thing that would help a lot would be to annul these copyright extensions. Copyright was just never supposed to last this long, and the result of it is that you can only comment on or include our shared culture, and the thing is culture builds on culture. It’s a living thing. It’s a lineage. It’s a heritage. And what these copyright extensions have done is made it only legal for the very, very rich to comment on culture. If you have enough money, yeah, you can, you know, put just about anything in your film. If you don’t, you can’t. And so one great thing to do would just be to — it’s even a really conservative thing to do — just maintain copyrights according to the terms that the works were created in.

I mean another thing is that it’s entirely possible that copyright extensions are violating artists’ moral rights, if they have any. It’s quite likely that a lot of the people that created these works in the ’20s and onwards, when they were signing over the rights, which they had to do in order to be published, they knew that the terms were only 28 years and so that could have been a comfort to them. Like, “Okay, I have to, you know, sign this over to a corporation, but it’s only gonna be 28 years and after 28 years, people can sing my song.”

And then, of course, if the corporation extended that then that would be 56 years and then, you know, with these like unlimited extensions it means never. So it’s entirely possible that had artists known that they wouldn’t have done this or, you know, there’s no way to get the consent of the artists from history to say, “Is it okay if we lock up your work forever and ever?” That really might not have been all right with them.

Art Brodsky: One of the items I read about is that your next project, speaking of copyright, after Sita was going to be some sort of project on copyright and copyright fundamentalism.

Nina Paley: Yes.

Art Brodsky: Tell us about it.

Nina Paley: Here. Here’s my…

[shows her shirt, which says “©ensorship” on the front]

Ta-da! (Laughter) That’s what I think of copyright. (Laughter) Yes, the Minute Memes. QuestionCopyright.org and I wrote out little descriptions of 12 of these little shorts, each of which will have a little song and cartoon, and they each deal with a fundamental aspect, or concept, related really to freedom of speech. They’re not specifically about copyright. They’re about freedom of speech.

Now copyright happens to be the main form of censorship in the West, so if you are concerned about freedom of speech, freedom of expression, you’re naturally gonna be dealing with these concepts that have to do with copyright that are misunderstood. And one of them is called “Copying Isn’t Theft.” And we aim to explain that copying isn’t theft, this radical concept that, yes, that is actually true. We hope to bring the laws of physics back into the discussion of copyrighting. That’s really what it is. The big media industries have been lobbying for so long. They have these massive propaganda campaigns that just say, “Copying is stealing. Copying is stealing. Copying is stealing.” And after enough years, people just go, “Copying is stealing.” It’s not stealing! It’s making another of something. It’s adding; it’s not subtracting (laughter). Copying is good. And I have a little song about that which I’m sure you’re gonna

ask me to sing…

Art Brodsky: Yes. We couldn’t get through this without it, Nina. You know that.

Nina Paley: All right. I’ll try to sing. I’m — as you can tell, I’m coughing.

[Singing]

Copying isn’t theft.

Stealing a thing means one less left.

Copying it makes one thing more.

That’s what copying’s for.

Copying isn’t theft.

If I copy yours, you have it, too.

One for me and one for you

That’s what copies can do.

If I steal your bicycle,

you have to take the bus;

but if I just copy it,

there’s one for each of us.

Making more of a thing,

that is what we call copying.

Sharing ideas with everyone,

that’s why copying is fun!

Art Brodsky: Fabulous, fabulous.

Nina Paley: Yes, we need to have this professionally recorded and arranged and —

Art Brodsky: And licensed.

Nina Paley: Hopefully — yeah, licensed. (Laughter)

Nina Paley: Yeah, it needs to be licensed. It needs to be ShareAlike-licensed.

[intermission animation]

Art Brodsky: Here’s the question. I mean we’re start… we touched on this. You know, copyright doesn’t seem to benefit you at all. It benefits the studios and the big moguls and everything but, you know, you seem to not have any benefit, and you’re theoretically one of the people that’s supposed to be protected by it, right?

Nina Paley: Right. And people keep saying, “Oh, well, copyright, it just comes down to money.” But it doesn’t. It comes down to control. The big studios are not making more money. I don’t think so. I don’t think so — I think that the total wealth is limited by copyright. What it does do for big studios, as I mentioned before, is it eliminates competition. When you have a system where only the extremely wealthy can create art or create media, then you shut out this huge number, this vast number of people that now have access to the technology to make that stuff. That’s what it does. It simply makes it not possible for independents to participate in mass culture.

Art Brodsky: Have you come across the orphan works issue in doing either your strips or your cartoons or other things?

Nina Paley: I know about it and because I’m a cartoonist, I know — you know, I hear from a lot of cartoonists who are such copyright fundamentalists for the most part. Which is really interesting — I think it’s because simply artists are vulnerable and terrified, and we’ve been told for so long that this is our source of power, we — you know, of course we want to believe that. We want to believe that we have this kind of power to tell other people what to do, but what we forget is that you need incredibly expensive lawyers. And I actually know small artists that take this gleeful joy in suing someone smaller than them. Like they find like some tiny, tiny little operator, you know, and it’s like, “Ha, ha, I sued them. I got them.” I know an animator who apparently — on the streets of New York someone was selling pirated DVDs of his film, and he just grabbed them all off of his table, and he was so proud of himself, you know, so proud of taking the day’s income away from this immigrant (laughter) this poor guy. But, you know, the seller was smaller than him, less powerful than him.

Art Brodsky: Yeah. When you did your shadow figures, were those ones you made up by yourself or were they from someplace else?

Nina Paley: Those are derivative works. Those were derived from designs of existing shadow puppets, traditional shadow puppets that I found in books and photographs and online and whatnot.

Art Brodsky: So you didn’t get into any trouble for those.

Nina Paley: Not yet. I could be, you know. It’s very unlikely. The designs are really traditional, so they’re not — they’re — it’s very unlikely that the copyrights are registered. On the other hand, I know that the World Intellectual Property Organization is trying to basically privatize all culture, that if we say, “Well, some stuff’s owned and some stuff’s not,” then it’s like, “Oh, well, the problem is that some stuff isn’t owned, so let’s just privatize absolutely everything and how we distribute that.” Well, we won’t… maybe there’ll be some problems there (laughter). We’ll probably distribute it the same way we’ve distributed the — you know, all the profits that come from corporate industrialization. (Laughter) We’ll just use that system.

Art Brodsky: Sure. Can we have a copyright-less world, I mean without it at all?

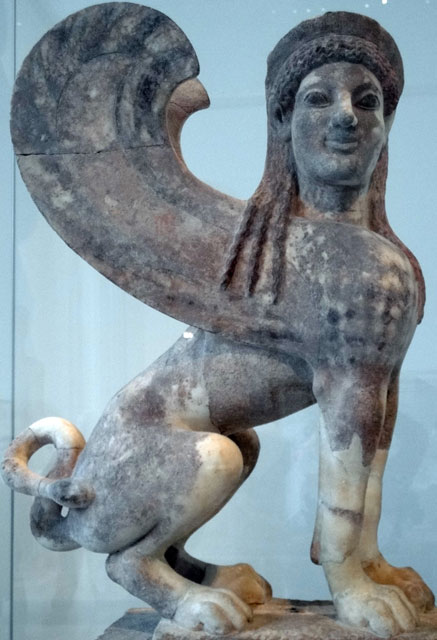

Nina Paley: We did. We did for the entire history of humankind. You know, many — most works, most like great works, that people refer to all the time were created, amazingly, without copyright! Beethoven worked without copyright, Bach, you know, like Mozart, Michelangelo… There was no copyright then. And yet somehow they created these brilliant works. How did they do it? They couldn’t do it today. And another thing about these brilliant works is that they’re not disconnected from the culture around them. They all are of their time. You know, perspective was around before Michelangelo. He didn’t invent that. You know, if you look at the whole history of art, there is a kind of evolution to it. You don’t have like cave paintings one day and then Michelangelo the next day. There’s this whole like gradual change in art. I mean it comes and goes. Cultures rise and fall, but artists are actually connected to the culture around them and they learn from other artists.

Art Brodsky: And with no entertainment lawyers in the middle to screw things up.

Nina Paley: Apparently not. Now people can say like, “Oh, well, that was when there were patrons or, you know, then there was the church.” The fact is that there… this gets like really complicated. I recommend reading the book “The Gift” by Lewis Hyde, even though unfortunately it’s copyrighted; hopefully he’ll come around. But artists historically and even currently have been supported by many, many means other than copyright and modern artists, except for perhaps the top, you know, one-half of 1 percent primarily are supported by means other than royalties.

In fact almost every artist I know is supported by some means other than royalties, and I looked at my entire career and realized I was not living — you know, that royalties amounted to almost nothing of the money I got. It was mostly commissions, grants, you know, work for hire, which I know is a terrible thing, but most artists do it. And it’s funny that copyright actually — copyright in a way makes even more people do work for hire, like they believe that — it’s like, “Oh, you shouldn’t do work for hire. You should sell your rights.” That’s the same thing. It’s exactly the same thing, licensing your — the rights to your work for a really long period of time. It’s the same thing as doing work for hire. You know, you can’t sell to someone else, you can’t let anybody else use it, you can’t share it, you can’t allow people to share it. That’s work for hire, you know. Your stuff is owned.

Art Brodsky: Well, Nina, thanks very much for taking the time to talk with us today. This has been a fabulous discussion, and I threatened when I saw you in New York to get you involved in stuff down here and this is the first step, but there will be more.

Nina Paley: Okay, I’ll come on down and testify. You can see I like to rant. I can take lessons or something.

Art Brodsky: You do. You can rant very well. We all appreciate that.

Nina Paley: (Laughter) I can also be very calm and sweet and stuff, but not when it comes to copyright.

Art Brodsky: Oh, but we wouldn’t want that.

Nina Paley: Okay, good. Okay, good.

Art Brodsky: You gotta show the artistic passion that’s in there for the films and everything.

Nina Paley: (Laughter) Yeah, I’m very passionate. Thanks very much, Art.

Art Brodsky: Bye.

![]() Over at Techdirt, Mike Masnick is naming names. We’re reposting his list below, but please visit his original article. (Techdirt is great on most of the issues we care about – I read it daily.)

Over at Techdirt, Mike Masnick is naming names. We’re reposting his list below, but please visit his original article. (Techdirt is great on most of the issues we care about – I read it daily.)