“Artists Should Be Compensated For Their Work”

(Translations: Polski.)

Nina Paley is the author of the freely-licensed hit animated film Sita Sings the Blues, among many other things, and is Artist in Residence at QuestionCopyright.org. She is also a committed Free Culture activist who writes frequently about copyright and how the permission culture affects art and artists.

This phrase comes up in many discussions of copyright: “Artists should be compensated for their art.” It is assumed that a) Artists are inherently entitled to monetary compensation for their Art, and b) copyright is a mechanism for this compensation.

I challenge both assumptions.

Of course, what people actually say is usually “Artists should be compensated for their work“. Below I’m going to distinguish between Art and Work, because confusing the two is exactly the problem.

a) Artists are inherently entitled to monetary compensation for their work.

I agree that artists are entitled to payment FOR THEIR WORK.

WORK is labor exchanged for money. Employer and worker negotiate a fee, the labor is performed, and the worker is paid. Many artists are workers: they are waiters, baristas, truck drivers. They should be compensated for their work, and they are, which is why they work.

Some artists perform a kind of skilled labor for money. This type of pre-negotiated labor is called a commission. Commissioned work is work, and artists are compensated for it, which is why artists take commissions.

But artists are not inherently entitled to monetary compensation FOR THEIR ART.

Art is a gift. An artist creates Art (not to be confused with skilled labor) on their own initiative. An artist “labors” in service of their vision, their Muse, the Art itself. The Muse alone is the Artist’s employer. It’s debatable whether the Artist can negotiate with their Muse before performing the labor — I certainly try to — but like most labor, terms are dictated by necessity. Just as economic necessity forces many workers into hard labor for low wages on their employer’s terms, so does suffering force many Artists into labor on the Muse’s terms. But unlike corporations and human employers, the Muse turns out to always have the artist’s best interests at heart. I’d much rather serve the Muse than an employer; but the Muse doesn’t negotiate a moneyed wage. Monetary compensation is not part of the deal.

The Muse “pays” me in Life. “Do this,” she says, “and you will Live. Turn away, and at best you will only survive.” I do have a choice: I can make the Art, or not. I accept the Muse’s terms. I perform the labor, and receive my “payment”: Life.

ART is negotiated with the MUSE. The “payment” is LIFE.

WORK is negotiated with an EMPLOYER. The payment is MONEY.

If artists want to be paid in MONEY, they should negotiate a fee before performing their work. That is the proper condition for payment. Or they can create work with no pre-negotiated payment, without demanding payment after the fact. That’s fine too. But to then demand payment after voluntarily working on your own terms — that is extortion.

Consider the Squeegee Man. He wipes windshields unbidden, then demands payment. He did the work; does he “deserve to be compensated”? Most would say no; if we wanted our windshields cleaned, we would negotiate this service in advance.

If I decide to sit behind a desk, take calls, devise flawed business plans, and lie, do I DESERVE to be compensated like a bank CEO? No. The bank CEO’s work was pre-negotiated. He gets $25 million in salary and bonuses because that was the deal BEFORE he sat down at his desk and did the work.

Does the bank CEO deserve his compensation? Well, most people are questioning that right now. I’m surprised it’s taken a massive financial crisis for that to happen, but at least folks are asking.

Since we’ve been in a massive artistic crisis for decades, maybe people have given up on asking whether the top .5% of artists deserve their monetary compensation. If I sing and prance around on stage, am I entitled to $110 million a year? It’s the same work Madonna does, and that’s what she makes. But Madonna arranged to be paid in advance of the singing and prancing, and performed it as work.

And if artists deserve to be compensated, then how much do they deserve? Isn’t art priceless? How do you determine how much it’s worth?

We could let the market decide. That could work… IF WE GET RID OF MONOPOLIES. The Free Market only works without monopolies. Information monopolies like copyright destroy that system. I’m all for allowing the Free Market to function, but it can only function without copyright.

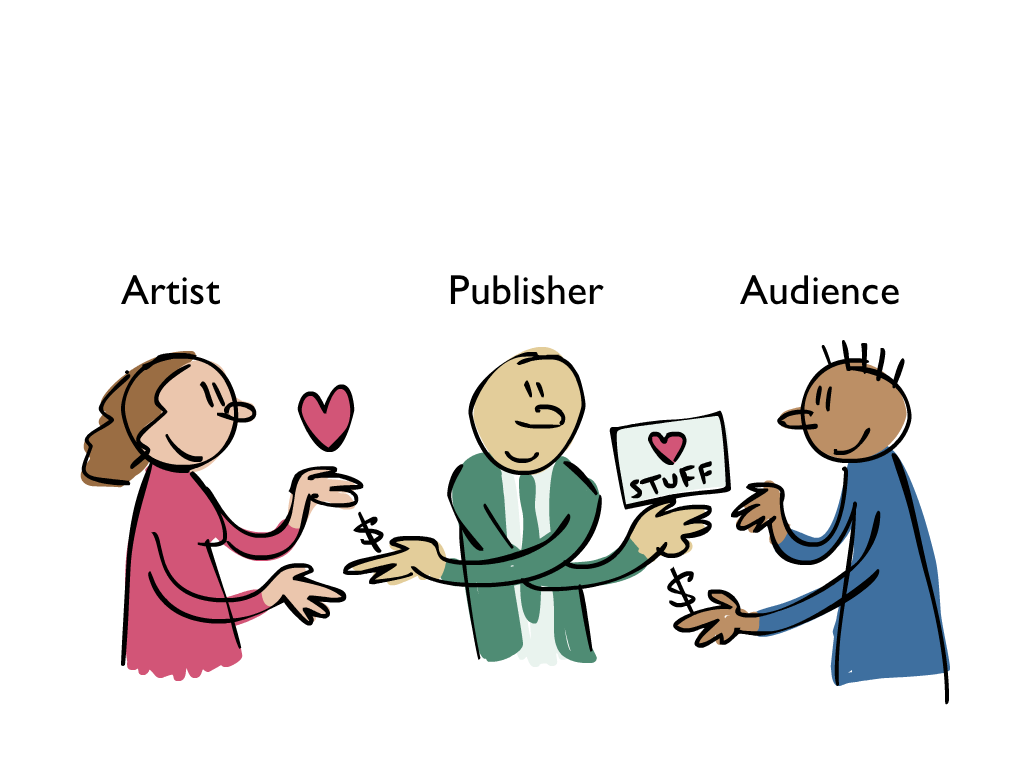

Indeed, Madonna is not compensated as an artist; she is reaping profits from her information monopoly — that is, the copyright that restricts her Art. So if Madonna is your model, you aren’t rooting for artists; you are rooting for monopolists. If your mechanism for “compensating” artists requires them to become monopolists and to grow and position their monopolies as monopolists do, then you are championing monopolies, not Art.

Art is not a commodity, it is a gift. If you want to produce a commodity, negotiate its worth in advance. Art is made on the initiative of the artist. Otherwise, it’s commissioned work, which obviously compensates the worker. But the the commissioner is often a corporation or investment group, who will expect a monopolist’s return on their investment. So the pro-copyright argument is simply in favor of maintaining the oligarchy whose elites happen to be the main patrons of art in our age. It’s like supporting monarchies because kings and queens patronize artists.

This may be hard to hear, but: many artists who claim they just want to eat and pay rent are lying (perhaps to themselves). Most artists don’t want a living wage — they want to win the lottery. Suggest to most filmmakers and musicians that “success” is about $75,000 a year, and they’ll turn up their noses. You call that a jackpot? They’re only in it for the millions, baby. If that means working a day job and remaining obscure, so be it. Millions need to be poor so that one can be rich; they’re willing to do their time being poor, so that one day they can be rich at the expense of others. Their turn will come, they think.

I suggest playing a different game entirely, because the lottery is a tax on people who are bad at math. But those kinds of artists want to play the lottery more than they want their art to reach people.

I do not mean to suggest that all artists have this attitude. There are also those who would be quite happy with a living wage; this is good, because that’s a much more realistic expectation for even a very talented artist. The problem is that our copyright discourse is dominated by the lottery attitude, such that when people say “Artists should be paid for the work” what they really mean is “All Art should be monopolized, so that some Artists can have a tiny chance of maybe getting rich one day.”

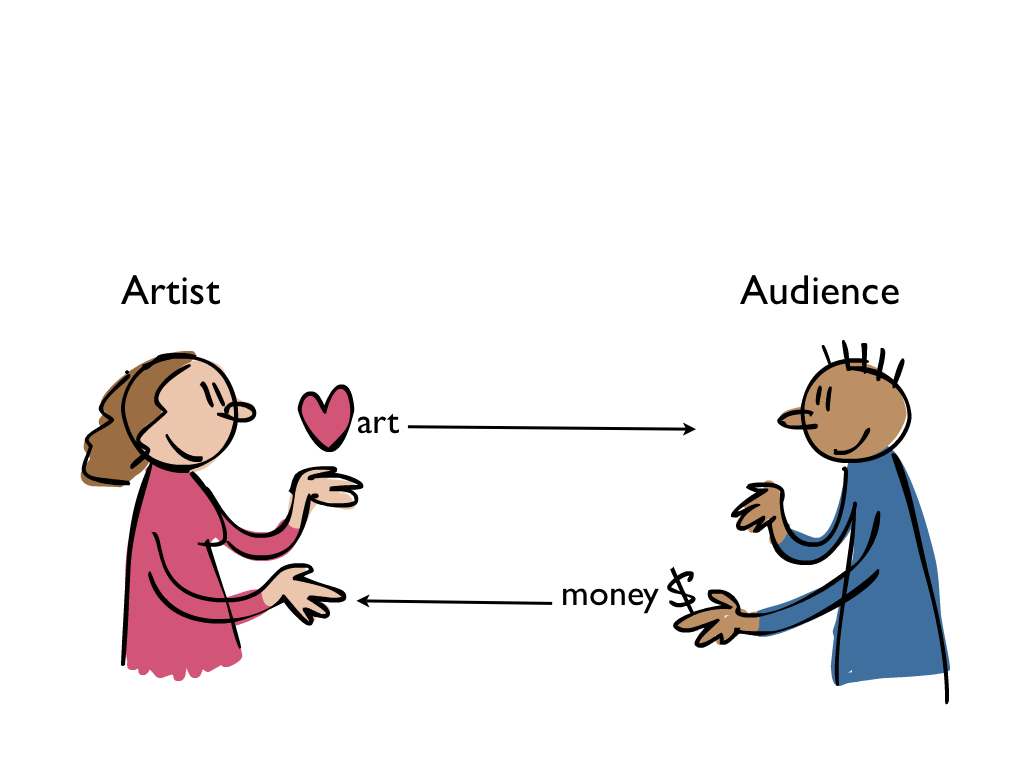

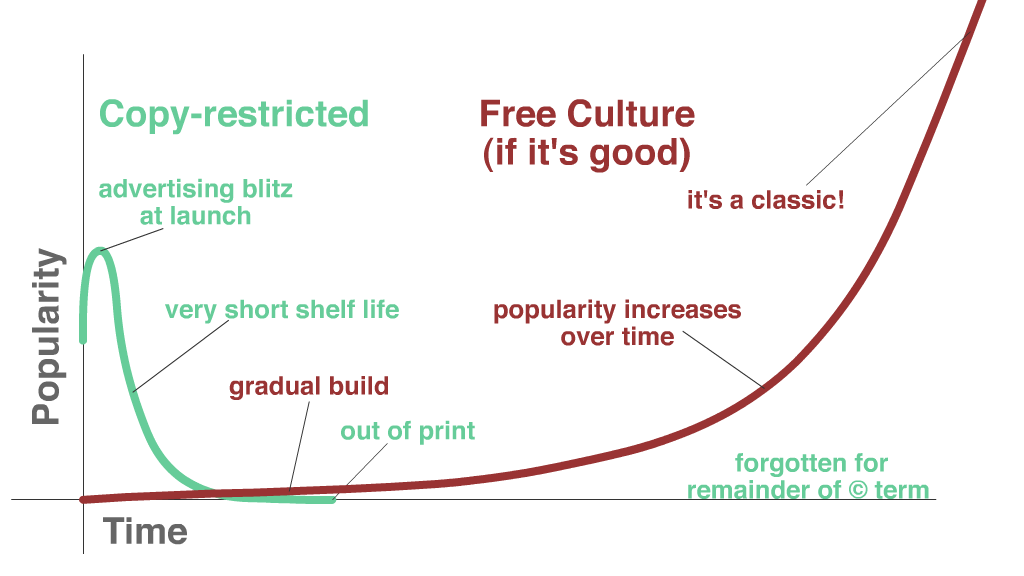

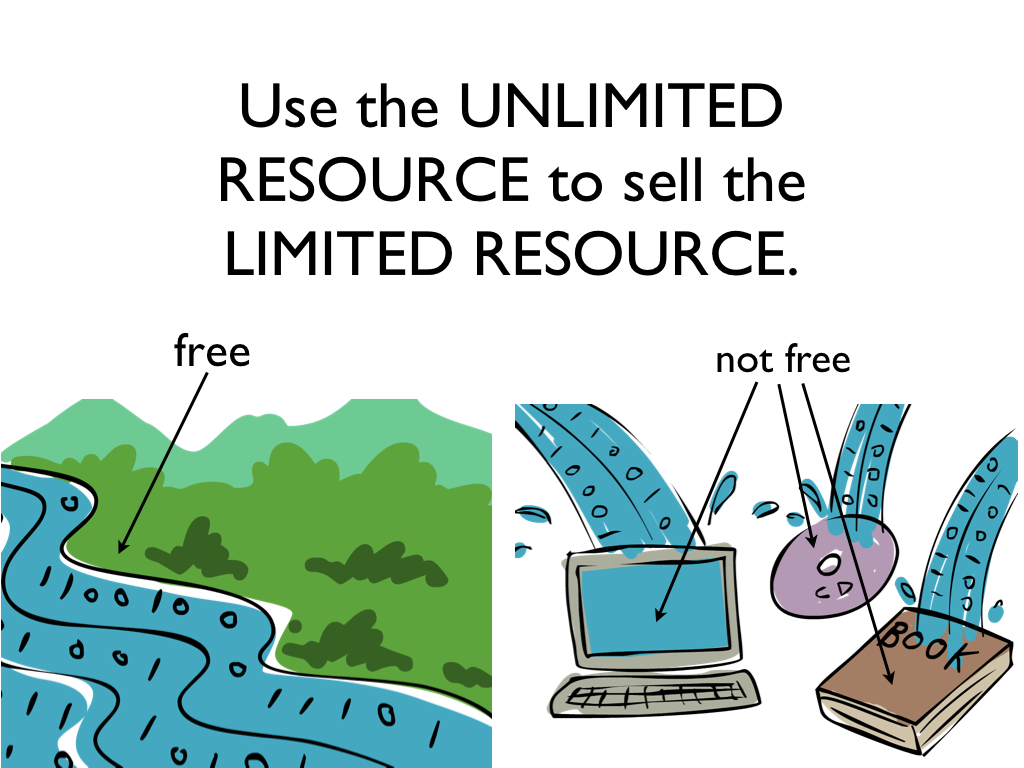

The best way for art to “compete” in a “free market” is to flow freely. The Internet makes it easy for an artist to give their work to an audience. It also makes it easy for audiences to return the gift. Giving is quite different from paying or being extorted. Money given is different from money coerced. It is a free transaction.

Not everyone will like a particular work of art. I don’t think people who dislike a work should be obligated to pay for it. Certainly works that offend, nauseate, or bore me, don’t inspire me to support their creators. But works that move and inspire me also move me to support their creators. I am touched by the Artist’s love, and want to offer something in return. Money is an obvious choice: the Artist can almost certainly use it. But it’s not always the right choice. I’m moved by many Beatles tunes, but I’m not inspired to send a check to Paul McCartney. He doesn’t need the money (not to mention he’s a big time monopolist). However, money is almost always an appropriate gift for a non-rich (read: typical) artist. It will be appreciated, and it’s not so personal as to be disturbing or threatening.

The Internet makes it very easy for fans to voluntarily send money to artists.

It’s really simple. Art competes with other art on the basis of quality. The Internet allows it to spread, to reach as many people as possible. Those who enjoy it have an easy mechanism to give back to the Artist if they are so moved. Not everyone will be so moved, nor should they be. Not everyone has to like everything. Not everything can touch us.

In conclusion:

Artists are NOT inherently entitled to monetary compensation for their Art. However we as a society can decide to support the Arts. The problem with this is that 95% of the Arts sucks. Most of us don’t want to be supporting artists that suck, nor allowing government committees to determine what is and is not worthy of support. My NYSCA grant rejection and its attendant comments have taught me never to trust government arts agencies. I’ll gladly accept funds from them, but I’m acutely aware that they aren’t reliably competent to separate the wheat from the chaff.

The best way society can support the Arts is to allow Art to spread, and to continue to encourage giving money to artists. That seems pretty natural to most people anyway, and it doesn’t infringe on anyone’s freedom.

(That’s how we get things like

(That’s how we get things like