The Liberation Point: Managing Monopolies for the Public Good

This proposal is a rewrite of one we first ran five years ago here at QCO. Since then, meaningful copyright (and patent) reform proposals have gradually been gaining ground. You know you’re making progress when someone gets fired from the U.S. Republican Study Committee for writing a policy brief that speaks sanely about copyright. Because the policy climate is changing, we’re re-introducing our proposal (cross-posted at Falkvinge on Infopolicy and the Center for the Study of Innovative Freedom) with an updated and clarified explanation. For many readers, it still won’t go far enough — it’s not abolition, for example. But proposals like this succeed first by reframing debate. In this case, the point is that if a government is going to offer private monopolies at all, it should at least reserve the public a way to ease them.

What would a truly free-market approach to copyrights and patents look like?

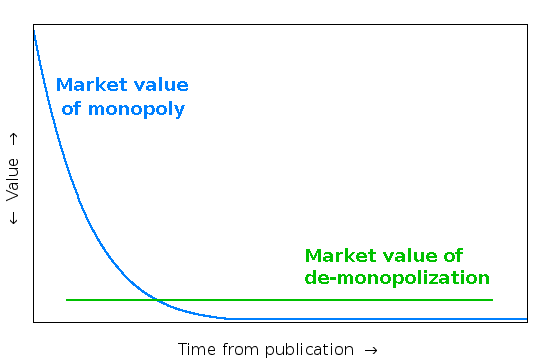

The problem we have right now is this:

The flat green line represents the value to the public of de-monopolizing the work — think of it as “what the public would be willing to pay for unrestricted access”. The point where the curved blue slope crosses the green line is the point where there is no longer any public or private purpose to having a monopoly. From that moment on, the value of the monopoly to the rights-owner is equal to or less than the value of de-monopolization. Yet today, the monopoly continues beyond that point. The green line is simply ignored in the current system: we pretend it does not exist.

You might think there’s already a market solution. After all, in the current system, anyone could in theory be offered a fixed sum to liberate their work into the public domain [1]. But markets don’t quite work the way we’d hope. This is is why we have eminent domain in real property, for example. As soon as someone starts talking about building an airport in some farm fields, all of a sudden every farmer decides their field is worth ten times as much as it was the day before, such that no airports could ever be built if we did not use the pre-rumor valuations. It is the same with copyrights and patents: the mere expression of interest in re-use drives up the price instantly, and the perpetual optimism of rights-holders ends up stretching their monopoly past its natural market end — hurting everyone else and preventing further re-use, yet frequently without realizing the benefit the rights-holder hoped for. We all lose.

But unlike with land, there’s a way out, because there’s a third thing we can do besides sell or not sell: we can liberate. That makes all the difference.

Finding The Liberation Point

Suppose things worked this way instead — I’ll use copyrights for the sake of discussion, but this applies to patents too:

A new work gets an initial automatic copyright term, as it does today but perhaps shorter: maybe a few months from publication, enough to ensure there’s time for the owner to register the work if they wish to extend the monopoly.

If the copyright owner does not register, the work simply enters the public domain [2].

If the copyright owner registers, then the copyright continues. Registration, which is renewable annually, requires paying a registration fee that is proportional to the current self-declared value of the work. That is, the copyright owner picks a number of dollars (yuan, euros, whatever) that she claims the work is worth. It can be any number at all, but the yearly registration fee will be a percentage of it — for discussion’s sake, say 1%. The exact proportions don’t matter here: it could be 0.5% or 2% instead of 1%, registration could be semi-yearly instead of yearly, etc. The idea is the same, regardless of how you set the knobs.

Now comes the key:

Since that declared value is now a matter of public record, anyone can pay that amount to the copyright owner to liberate the work into the public domain. This is not a purchase, it is a liberation. Prior to liberation — whether it comes through payment or through term expiration — people would still be free to sell or lease their copyrights, for whatever price they can get (which, interestingly, may be higher or lower than the registered value — the market dynamics behind that decision are just as rich as those involved in determining exclusivity value under today’s copyright system). But whoever the owner is, whether the author or someone else, they’re responsible for keeping up the registration. And while the work is still under registration, anyone can come along and pay the registered owner the declared value to liberate it.

Liberation, unlike purchase or lease, is a mandatory transaction. The justification is that since the registrant chose the price in the first place, it is by definition fair: it was self-declared. Furthermore, these are after all public monopolies, and the public’s ultimate interest is in having works be available without restriction. For governments to hand out monopolies with no escape clause has always been an abdication of responsibility. If there is a way to fix that, we should take it.

The copyright holder has an incentive not to declare too high a value, because she’ll have to pay a percentage of it to register; she has an incentive not to declare too low, because then someone will come along and liberate the work very quickly at a low price (though some artists will find that liberation is economically a better deal for them anyway, and simply not register, or register at a declared value of zero in order to get a timestamp for attribution purposes).

Because the value of a work may change over time, the registrant may adjust the declared value up or down each year when renewing the registration [3]. This is also one of the reasons behind that brief initial registration-free monopoly term: it gives the copyright holder a chance to judge the work’s monopoly value, information she can use to decide how much to register the work for.

Whether indefinite renewal should be available is an open question. Personally I think not, for two reasons: first, because there has simply never been a compelling argument for perpetual copyright and most jurisdictions do not have it. Second, because awareness of an approaching horizon will pressure registrants to set lower liberation prices as that horizon comes closer — which is the right direction for things to move, from the public’s point of view, since even the most confident authors cannot reliably predict years ahead of time which monopolies will remain valuable, and therefore far-future valuations do not have a significant incentivizing effect anyway.

But even if indefinite renewal were permitted, the system still has desirable effects. The tendency of monopolies to accumulate in media conglomerates (who then press for Internet censorship to preserve those monopolies) would be greatly lessened by the cost of maintaining all those registrations. Forced to choose which assets are really valuable, the companies would have to lower the liberation values for many works, thus providing the fertile ground for re-use and innovation that artists, other publishers, and the rest of us are denied under the current system.

On “Balance”

While this proposal is a compromise, it’s at least a compromise tilted toward the public interest. By analogy, think of a homeowner who cuts a driveway opening onto a public street in order to gain access to a private garage. If I take a streetside parking space away from the public, I expect to pay the city (that is, the public) a fee, and usually annually, too, not just a one-time fee. Similarly, a copyright owner who wants to keep a work out of the public domain should pay for that privilege. But unlike a garage, this privilege need not be permanent, because losing monopoly control over a work is not as serious as losing one’s indoor parking space.

This system would go a long way toward alleviating the orphan works problem, by ensuring that the copyright owner of a work could always be found (someone must be paying the fees over at the registry), and toward alleviating the ghost works problem (in which derivative works are suppressed), by setting a maximum amount of money that, in the age of Kickstarter, would usually still be attainable by a motivated party who wanted to see that work in the public domain.

The copyright lobby frequently talks of finding an appropriate “balance” between the needs of creators and the needs of the public. Like many appeals to balance, it is a smokescreen for something else: in this case, for efforts to increase copyright terms and restrictions beyond their already absurd lengths. The “balance” they’re talking about neatly presupposes that creators and the public are somehow on opposite sides, while multinational content monopoly conglomerates are, curiously, absent from the picture altogether. (Their portrayal is also historically suspect, as copyright was primarily designed to subsidize distributors not creators anyway.)

Thanks to this focus on exclusivity-based balance, proposals to improve the system are usually minor tweaks: broader “fair use” rights, a more thorough prior-art discovery process, various changes in scope, etc. But these approaches leave the basic problem untouched: when a copyright or patent is granted today, it creates a monopoly with no countervailing pressure towards a true free market.

There needs to be a market-based representation of the value of de-monopolization, expressible by those whom de-monopolization benefits. In Macaulay’s famous words, “the effect of monopoly generally is to make articles scarce, to make them dear, and to make them bad.” [4] Anyone familiar with, for example, the mess George Lucas made of his monopoly on the “Star Wars” movies will instantly see Macaulay’s point. The problem is not that Lucas botched the sequels, but that the Lucasfilm monopoly prevents anyone else from doing better. This is the problem with monopolies generally — it’s not what they let the monopoly owner do, it’s what they don’t let others do. Monopolies are the opposite of free markets.

The Liberation Point system introduces de-monopolization as a market force, without involving the government in pricing decisions, term-length calibrations, or other arbitrary regulatory judgements [5]. The system takes “balance” seriously: it gives the rights-holder a decisive role in setting a valuation and benefitting from it, but at the same time represents the public’s interest in not having works monopolized forever. Crucially, it avoids the need for complicated regulatory formulas, which would inevitably create a target surface for monopoly interests to aim lobbying power at. Instead, it gives the public a mechanism for representing its own interests directly, with the government limited to a bookkeeping role.

The proposal is not merely rhetorical. I would be delighted, if surprised, for it to receive legislative interest. But it is also meant to expand the range of the possible. Fiddling with copyright term lengths and improving the Patent Office’s processes feel good, but they are fundamentally repainting a burning barn. To get lasting improvement, we need to permanently reduce the “lobbyability” of the system as a whole. The Liberation Point method is one way to do that [6], and to show that market-tempered monopoly is possible in principle. It’s high time these kinds of solutions were on the table.

References:

[1] The term “public domain” is used informally here. It is a term of art in copyright law more than in patent law, but it is easy to intuitively understand what it would mean for patents: that no one has a monopoly, that is, there is no one with the power to restrict usage.

[2] There should be nothing shocking about this: the public domain is the natural destination for works, and even most proponents of lengthening copyright and patent terms pay lip service to that goal. Furthermore, registration requirements used to be the norm if one wanted to hold any public monopoly. Indeed, the requirement for copyrights was only eliminated under the theory that insisting on registration gave advantage to corporations who had economies of scale to streamline the paperwork involved in filing — which was probably true, in the days before the Internet, but today registration would be as easy as uploading a file and receiving a digitally-signed timestamp.

[3] Alternatively, the owner could be allowed to adjust the declared value at any time (perhaps even as a reaction to liberation offers), with the provision that any upward adjustment would require immediate payment of the difference between the old and new registration fees. However, the public domain would probably be better served by simply allowing adjustment only at fixed intervals: if the owner of a work can’t figure out its market value and set the fee accordingly, that is no reason to favor the owner over the public when the work is being liberated at a price the owner clearly once thought sufficient.

[4] en.wikisource.org/wiki/Copyright_Law_(Macaulay)

[5] One of the problems with not having a systematized and predictable path to de-monopolization is that we instead get unpredictable decisions like India’s decision to set a compulsory license rate on a drug still under patent. The point is not that the Indian government made a mistake — the decision was quite defensible — but that handling each such instance as a special case inevitably leads to lack of predictability and, eventually, to corruption. Yet it’s governments that issue patent monopolies in the first place: if they can set compulsory license rates in specific cases, then they can offer a mechanism for de-monopolization in the general case.

[6] My colleague Nina Paley has suggested a simpler system: bring back registration, and set the fee for the first year at $1, the second year at $2, the third year at $4, then $8, $16, $32, $64, and so on. This has the advantage of immediate comprehensibility, and it’s clearly effective at tempering the monopoly: very few works would remain restricted past the 20 year mark, and her system doesn’t need to be adjusted for inflation for a long time.

[7] For works released under a free license, the fee should be waived, and indeed the requirement to register or renew at all should be waived, because such licenses are non-monopolistic by definition. For simplicity’s sake I did not mention this in the original proposal. Richard Stallman immediately noticed the problem; I thank him for pointing it out, as that reminded me to add this footnote.