(Translations: 中文)

Today the Vancouver Sun published an editorial by Jacob Tummon entitled “The Case for the Death of Copyright”. Tummon is already known to readers here for his in-depth piece on copyright at Legaltree.ca. While this editorial is necessarily shorter and less detailed than that earlier piece, it still makes a strong case. Tummon is a law school graduate, and he makes the excellent point that unenforceable laws inevitably lead to disrespect for the law itself: “Canada has experience with laws that engender widespread violation: Consider prohibition in the 1920s. A law violated so brazenly is more than meaningless — it undermines the effectiveness of the legal system generally.” Bravo to the Vancouver Sun for giving space to these ideas.

Here’s the full editorial, reprinted with Jacob Tummon’s permission…

The Case for the Death of Copyright

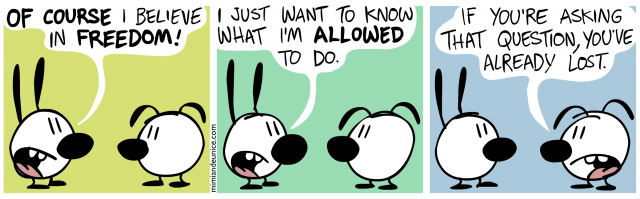

It has been said that intellectual property law has an unfortunate tendency to “disable critical thought.”

Nowhere is this more apparent than the reasons proffered for copyright in the Internet age, including the refrain that “copying is tantamount to stealing.” That flatly is not the case.

The morality, economics, and practicality of laws dealing with physical property do not hold for the intangible works covered by copyright. With finite physical property, scarcity is inescapable; with digital representations, scarcity does not apply. It is therefore not surprising that reasoning premised on this false analogy yields a law not in the best interests of content creators (“content creator” means artists, musicians, writers and so forth.)

The ostensible justification for copyright is that it provides attribution to the original creator and serves as an economic incentive for creators who can license the use of their work to make money, provided someone is willing to pay.

The latter point deserves careful scrutiny as the vast majority of creators do not earn meaningful incomes through copyright. Moreover, there are viable models for creators to earn income from their work which do not depend on copyright. Sponsorships, ticket sales, T-shirt sales and commissioned works are obvious longstanding examples.

Canadian musician Jane Siberry offers her music on her website using a “pay what you can” system, but a guideline shows the average price customers have paid per track. The result is an average price higher than what one would pay through iTunes. There are also similarly clever business models for novelists.

Embedding advertising or product placement within a TV show or movie is another viable means to pay for content. Budweiser produces its own TV-type shows on its website Bud.TV. Budweiser’s motive is worth noting for its prescient thinking: “If we don’t start playing in this digital game now we’re going to be playing catch-up for a long time. And this is an industry that can’t afford catch-up,” explained Tony Ponturo, Anheuser-Busch’s vice-president of global media and sports marketing.

Nor is proper attribution dependent on copyright. Tort law, through causes of actions like defamation and passing-off, could be wielded to prevent someone other than the original creator from claiming authorship, and also the original creator being credited with an altered version of the work. Incidentally, plagiarism in an academic setting is currently enforced independently of copyright.

Trademarks and patents are other areas of intellectual property that do not depend on copyright and would continue to exist in the absence of copyright.

That copyright isn’t needed for attribution or economic incentive is not the whole story. There is a body of work, in all areas covered by copyright, which requires the elimination of copyright to flourish. DJ’s making mixed tapes is a simple example.

Consider, with the means available through modern software, the splicing of video to say nothing of novels; a freeing from the constraints of copyright would invariably lead to an explosion of works being altered, transformed, improved, and ultimately morphed into new works.

The lack of such creative works is a not insignificant cost of copyright. This repressing effect can be damaging to the promotion of political and social expression and greater productivity.

Copyright was originally created as a means for government to exercise censorship after the advent of the movable type printing press. Given this origin it is not surprising that copyright is not intellectually coherent.

Stephen Breyer, now a judge on the U.S. Supreme Court, wrote as an academic in the 1970s on the weak case for copyright, asking why the work covered by copyright should be treated differently than other actions that produce value far beyond what they get remuneration for, i.e. the person who invents the supermarket, the person who clears a swamp, a schoolteacher.

The truth is that copyright has traditionally, and to this day, served primarily the publisher’s interest and not that of the creator or the public — it is not derived from natural justice.

Irrespective of moral and economic dimensions, the deathblow to copyright will likely come from the Internet itself. Due to the nature of the Internet, and anonymizing technologies in particular, the practicality of attempting to enforce a pre-internet copyright regime through the Internet is a road that we as a society should not go down.

Canada has experience with laws that engender widespread violation: Consider prohibition in the 1920s. A law violated so brazenly is more than meaningless — it undermines the effectiveness of the legal system generally.

Over time, the Internet will increasingly expose constraints on text, pictures, and videos for what they are — arbitrary and outmoded. In the meantime, it makes sense for Canada not to pass copyright laws that are more restrictive and invasive.

Jacob Tummon is a recent graduate of the University of British Columbia’s faculty of law.