Announcing BookLiberator Beta.

Announcing BookLiberator Beta — the affordable, low-tech book digitizer that’s made of wood, looks good in your living room or library, and can scan 600-900 pages per hour!

Order now from our online store

We’re very pleased to announce the availability of BookLiberator Beta kits. This is a project we’ve been working on for some time, and it’s very important to us.

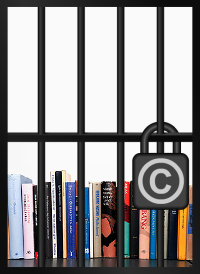

We’ve always known that whenever people feel the effects of copyright restrictions directly, in their own lives, they inevitably start questioning those restrictions. The goal of the BookLiberator project is to enable people to encounter those restrictions more often, in more situations, so they’ll ask the same questions we ask here at Question Copyright.

BookLiberator Beta is the early-adopter release of what will eventually be BookLiberator 1.0. Please note that the Beta version comes without cameras — the 1.0 version will have cameras, but first we have to learn which cameras work best, and that’s where the early adopters come in. Any modern consumer-grade digital cameras will fit, as long as they accept a standard screw-in camera mount. Once the brave beta testers have reported field results, we’ll be able to offer appropriate camera options for the 1.0 manufacturing run.

If all this sounds like something you want to get involved in, please see BookLiberator.com for more information. Remember, any scans you make now can be reprocessed as many times in the future as you want; as software improves and becomes better able to extract text from images, you can just rerun your old images through newer software.

Video of a BookLiberator usage demonstration, at a HOPE conference:

There are many perfectly lawful uses of a book digitizer, of course. We encourage people to use their BookLiberators to liberate text and images from the printed page in

- Public domain works;

- Works under Free Culture licenses;

- Works for which one has (for whatever reason) special exemption from the usual restrictions on copying, sharing, and sharing modified copies;

- Works for which the digitization constitutes “fair use“.

We’re glad the BookLiberator can be used for all those things, but that’s not really why we’re selling it. We’re selling it because we want people to have one more route by which to experience copyright restrictions. We want people to look longingly at their bookshelf and be reminded of why they can’t work with digital copies of most of their books. We want them to realize that the only thing preventing them from liberating that text from the tree pulp on which it rests is an increasingly problematic law that does much to support monopoly-based distribution industries while doing little to support artists (indeed, while often harming artists — learn more here).

We don’t endorse the use of the BookLiberator to engage in unauthorized copying, and we strongly discourage you from using it that way. Our goal is for people to not make such copies — to feel the handcuffs that prevent them from doing so, and to debate whether those handcuffs are a good idea.

Join us in feeling the pain. Order your BookLiberator Beta kit today.

A band of researchers has been tirelessly trying to demonstrate that a body of scientific work which rests on a paper from over 10 years ago is completely wrong. The only problem is, their argument isn’t being allowed to stand or fall on its merits — instead, copyright restrictions are interfering with their ability to make their case at all.

A band of researchers has been tirelessly trying to demonstrate that a body of scientific work which rests on a paper from over 10 years ago is completely wrong. The only problem is, their argument isn’t being allowed to stand or fall on its merits — instead, copyright restrictions are interfering with their ability to make their case at all. At QCO we make a point of calling things by their right names, and of encouraging others to do so. For example, we always talk about “

At QCO we make a point of calling things by their right names, and of encouraging others to do so. For example, we always talk about “